So far in the “Field Guide” series, we’ve mainly looked at critical infrastructure systems that, while often blending into the scenery, are easily observable once you know where to look. From the substations, transmission lines, and local distribution systems that make up the electrical grid to cell towers and even weigh stations, most of what we’ve covered so far are mega-scale engineering projects that are critical to modern life, each of which you can get a good look at while you’re tooling down the road in a car.

This time around, though, we’re going to switch things up a bit and discuss a less-obvious but vitally important infrastructure system: the cold chain. While you might never have heard the term, you’ve certainly seen most of the major components at one time or another, and if you’ve ever enjoyed fresh fruit in the dead of winter or microwaved a frozen burrito for dinner, you’ve taken advantage of a globe-spanning system that makes sure environmentally sensitive products can be safely stored and transported.

What’s A Cold Chain?

Simply put, the cold chain is a supply chain that’s capable of handling items that are likely to be damaged or destroyed unless they’re kept within a specific temperature range. The bulk of the cold chain is devoted to products intended for human consumption, mainly food but also pharmaceuticals and vaccines. Certain non-consumables also fall under the cold chain umbrella, including cosmetics, personal care products, and even things like cut flowers and vegetable seedlings. We’ll be mainly looking at the food cold chain for this article, though, since it uses most of the major components of a cold chain.

As the name implies, the cold chain is designed to maintain a fixed temperature over the entire life of a product. “Farm to fork” is a term often used to describe the cold chain, since the moment produce is harvested or prepared foods are manufactured, the clock starts ticking. The exact temperature required varies by food type. Many fruits and vegetables that ripen in the summer or early autumn can stand pretty high temperatures, at least for a while after harvesting, but some produce, like lettuces and fresh greens, will start wilting very quickly after harvest.

For extremely sensitive crops, the cold chain might start almost the second the crop is harvested. Highly perishable crops such as sweet corn, greens, asparagus, and peas require rapid cooling to remove field heat and to slow the biological processes that were still occurring within the plant tissues at the time of harvest. This is often accomplished right in the field with a hydrocooler, which uses showers or flumes of chilled water. Extremely perishable crops such as broccoli might even be placed directly into flaked ice in the field. Other, less-sensitive crops that can wait an hour or two will enter the cold chain only when they’re trucked a short distance to an initial processing plant.

Many foods, including different kinds of produce, fresh meat and fish, and lots of prepared meals, benefit from flash freezing. Flash freezing aims to reduce damage to the food by controlling the size and number of ice crystals that form within the cells of the plant or animal tissue. Simply putting a food item in a freezer and waiting for the heat to passively transfer out of it tends to form few but large ice crystals, which are far more damaging than the many tiny ice crystals that form when the heat is rapidly removed. Flash freezing methods include cryogenic baths using liquid nitrogen or liquid carbon dioxide, blast cooling with high-velocity jets of chilled air, fluidized bed cooling, where pressurized chilled air is directed upward through a bed of produce while it’s being agitated, and plate cooling, where chilled metal plates lightly contact flat, thin foods such as pizza or sliced fish.

Big and Cold

Once food is chilled to the proper temperature, it needs to be kept at that temperature until it can be sold. This is where cold warehousing comes in, an important part of the cold chain that provides controlled-temperature storage space that individual producers simply can’t afford to maintain. The problem for farmers is that many crops are determinate, meaning that all the fruits or vegetables are ready for harvest more or less at the same time. Outsourcing their cold warehousing to companies that specialize in that part of the cold chain allows them to concentrate on growing and harvesting their crop instead of having to maintain a huge amount of storage space, which would sit unused for the entire growing season.

Cold warehouses, or public refrigerated warehouses (PRWs) as they’re known in the trade, benefit greatly from economies of scale, and since they accept produce from hundreds or even thousands of producers, their physical footprints can be staggering. The average PRW in the United States has grown in size dramatically since the post-pandemic e-commerce boom and now covers almost 185,000 square feet, or more than 4 acres. Most PRWs have four temperature zones: deep freeze (-20°F to -10°F) for items such as ice cream and frozen vegetables; freezer (0°F to 10°F) for meats and prepared foods; refrigerated (35°F to 45°F), for fresh fruits and vegetables; and cool storage, which is basically just consistent room-temperature storage for shelf-stable food items. What’s more, each zone can have sub-zones tailored specifically for foods that prefer a specific temperature; bananas, for example, do best around 46°F, making the fridge section too cold and the cool section too warm. Sub-zones allow goods to be stored just right.

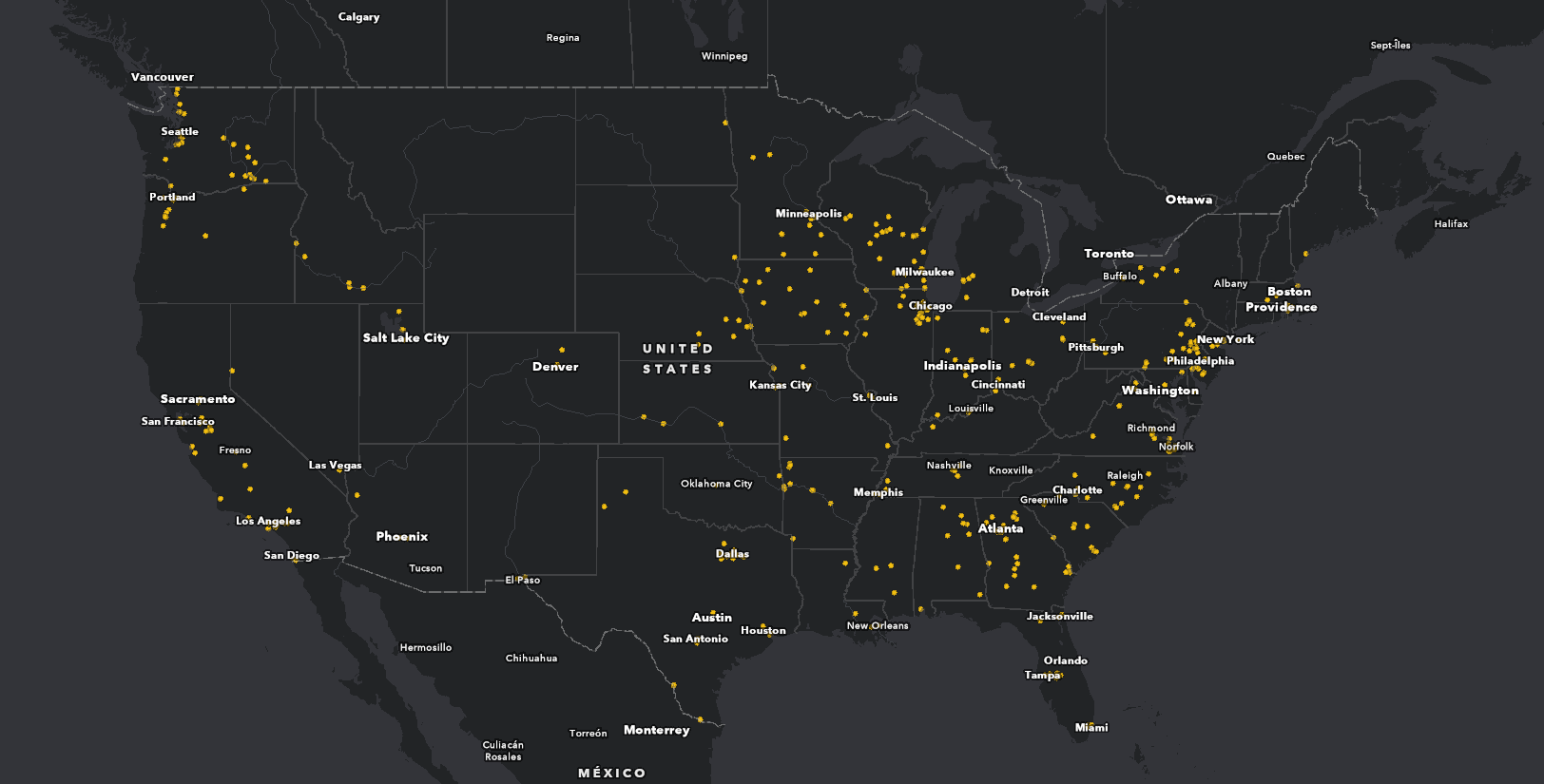

Due to the nature of their business, location is critical to PRWs. They have to be close to where the food is produced as well as handy to transportation hubs, which means you’ve probably seen one of these behemoth buildings from a highway and not even known it. The map above highlights the main agricultural regions of the United States, such as the fruit and vegetable producers in the Central Valley of California and the Willamette Valley in Oregon, meat packing plants in the Upper Midwest, the hog and chicken producers in the South, and seafood producers along both coasts. It also shows a couple of areas with no PRWs, which are areas where agriculture is limited to cereal grains, which don’t require refrigeration after harvest, and livestock, which are usually shipped for slaughter somewhere other than where they were raised.

Thanks to the complicated logistics of managing multiple shippers and receivers, most cold warehouses have a level of automation that rivals that of an Amazon distribution center. A lot of the automation is found in the high-bay freezer, a space often three or four stories tall that has rack after rack of space for storing palletized products. Automated storage and retrieval systems (AS/RS) store and fetch pallets using large X-Y gantry systems running between the racks. Algorithms determine the best storage location for pallets based on their contents, the temperature regime they require, and the predicted length of stay within the warehouse.

While AS/RS reduces the number of workers needed to run a cold warehouse, and there are some fully automated PRWs, most cold warehouses maintain a large workforce to run forklifts, pick pallets, and assemble orders for shipping. These workers face significant health and safety challenges, risking everything from slips and falls on icy patches to trench foot and chill-induced arthritis and dermatitis. Cold-stress injuries, such as hypothermia and frostbite, are possible too. Warehouses often have to limit the number of hours their employees work in the cold zones, and they have to provide thermal wear along with the standard complement of PPE.

Reefer Madness

Once an order is assembled and ready to ship from the cold warehouse, food enters perhaps the most visible — and riskiest — link in the cold chain: refrigerated trucks and shipping containers. Known as reefers, these are specialized vehicles that have the difficult task of keeping their contents at a constant temperature no matter what the outside conditions might be. A reefer might have to deliver a load of table grapes from a PRW in California to a supermarket distribution center in Massachusetts, continue to Maine to pick up a load of live lobsters, and drop that off at a PRW in Florida before running a load of oranges to Washington.

Meeting the challenge of all these conditions is the job of the refrigeration unit. Typically mounted in an aerodynamic fairing on the front of a semi-trailer unit, the refrigeration unit is essentially a heat pump on steroids. For over-the-road (OTR) reefers, as opposed to railcar reefers or shipping container reefers, the refrigeration unit is powered by a small but powerful diesel engine. Typically either three- or four-cylinder engines making 20 to 30 horsepower, these engines run the compressor that pumps the refrigerant through the condenser and evaporator, as well as the powerful fan that circulates air inside the trailer. Fuel for the engine is stored in a tank mounted under the trailer, allowing the reefer to run even when the trailer is parked with no tractor attached. The refrigeration unit is completely automatic, with a computer taking input from temperature sensors inside the trailer to make sure the interior remains at the setpoint. The computer also logs everything going on in the reefer, making the data available via a USB drive or to a central dispatcher via a telematics link.

The trailer body itself is carefully engineered, with thick insulation to minimize heat transfer to and from the outside environment while maximizing heat transfer between the produce and the air inside the trailer. For maximum cooling — or heating; if a load of bananas has to be kept at their happy place of 46°F while being trucked across eastern Wyoming in January, the refrigeration unit will probably have to run its cycle in reverse to add heat to the trailer — the air must reach the back of the unit. Reefer units use flexible ducts in the ceiling to direct the air 48 to 53 feet to the very back of the trailer, where it bounces off the rear doors and returns to the front of the trailer with the help of channels built into the floor. Shippers need to be careful when loading a reefer to obey load height limits and to correctly orient pallets so as not to block air circulation inside the trailer.

In addition to the data logging provided by the refrigeration unit, shippers will often include temperature loggers inside their shipments. Known generically to produce truckers as a “Ryan” for a popular brand, these analog strip chart recorders use a battery-powered motor to move a strip of paper past a bimetallic arm. Placed in a tamper-evident container, the recorder is placed within a pallet and records the temperature over a 10- to 40-day period. The receiver can break the seal open and see a complete temperature history of the shipment, detecting any accidental (or intentional; drivers sometimes find it hard to sleep with the reefer motor roaring right behind the sleeper cab) interruptions in the operation of the reefer.

Featured image: “Close Up of Frozen Vegetables” by Tohid Hashemkhani