On this date in 1975, a Soviet and an American shook hands. Even for the time period, this wouldn’t have been a big deal if it wasn’t for the fact that it happened approximately 220 kilometers (136 miles) over the surface of the Earth.

Although their spacecraft actually launched a few days earlier on the 15th, today marks 50 years since American astronauts Thomas Stafford, Vance Brand, and Donald “Deke” Slayton docked their Apollo spacecraft to a specifically modified Soyuz crewed by Cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Valery Kubasov. The two craft were connected for nearly two days, during which time the combined crew was able to freely move between them. The conducted scientific experiments, exchanged flags, and ate shared meals together.

Politically, this very public display of goodwill between the Soviet Union and the United States helped ease geopolitical tensions. On a technical level, it not only demonstrated a number of firsts, but marked a new era of international cooperation in space. While the Space Race saw the two counties approach spaceflight as a competition, from this point on, it would largely be treated as a collaborative endeavour.

The Apollo–Soyuz Test Project lead directly to the Shuttle–Mir missions of the 1990s, which in turn was a stepping stone towards the International Space Station. Not just because that handshake back in 1975 helped establish a spirit of cooperation between the two space-fairing nations, but because it introduced a piece of equipment that’s still being used five decades later — the Androgynous Peripheral Attach System (APAS) docking system.

Meeting in the Middle

While the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project was the first time spacecraft from two different countries linked up, it was far from the first docking in space. The Apollo program relied heavily on the concept, as the Command Module and Lunar Module would dock and undock multiple times on each lunar mission. For their part, the Soviets had also docked a pair of Soyuz capsules together as early as 1967. By the early 1970s, both nations had also docked spacecraft to their respective space stations.

The problem was, the docking systems used by both countries weren’t compatible with each other. In fact, things were changing so fast that even vehicles from the same country couldn’t necessarily dock with each other. For example, an American Gemini capsule wouldn’t be able to dock with Skylab. Of course, this isn’t terribly surprising. At this point, most of the hardware was mission-specific, and only flew once.

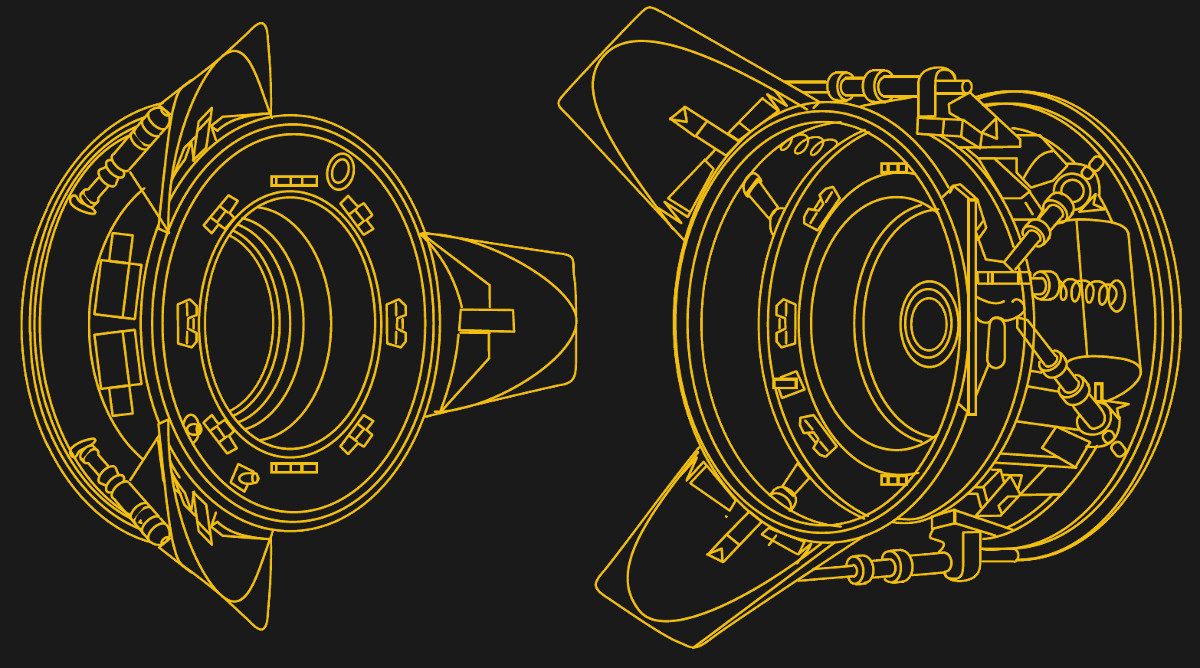

What was the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project needed was a standardized docking interface that took into account the lessons learned by both countries so far. By 1970, Soviet and US engineers had started meeting and exchanging information to decide what such a docking standard would look like. It was decided early on that this new docking standard should be androgynous — rather than having distinct “male” and “female” variants as was the norm with earlier docking ports. In this way, the same docking port could be used to support two spacecraft docking together as was planned for the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project, while at the same time allowing a vehicle to dock to a space station.

This capability was so key to the design that the docking standard ultimately came to be known as the Androgynous Peripheral Attach System. While the US and Soviet versions did differ slightly, they were mechanically compatible with each other. Some elements of the design were the result of a compromise, such as the overall diameter of the port being limited to the size of the existing Apollo and Soyuz capsules, but otherwise it was hoped the concept would prove useful for future missions and spacecraft from both nations.

Built to Last

The Apollo–Soyuz Test Project was the only time an Apollo and Soyuz spacecraft docked in space. In fact, it was the last time an Apollo spacecraft flew — after the conclusion of this mission, there wouldn’t be anther crewed American mission until the Space Shuttle came online nearly six years later.

But once the Americans started flying the Shuttle, and the Soviets had established their Mir space station, it wasn’t long before the two would meet. The Soviets had already designed a modified version of APAS that they called APAS-89, which was intended to allow the Buran spacecraft to dock with Mir. Buran never made it past the testing phase, but the work on the docking port ended up being adapted once more for the Shuttle. This final version of the standard became known as APAS-95, and was used until the final Shuttle-Mir mission in June of 1998.

APAS-95 performed so well during the Mir missions that it was decided the Shuttle would continue to use it for the International Space Station. In addition, APAS-95 (as well as a modified “hybrid” version) would also be used to hold together the core US and Russian modules of the Station.

It was the defacto docking standard used until the introduction of the International Docking Adapter in 2015, which converted the exposed APAS-95 ports used for visiting American spacecraft to a newer design to be used by modern vehicles such as the SpaceX Dragon and Boeing Starliner.

While it has now been retired for the International Docking System Standard (IDSS), the ISS is still being held together by APAS-95, and will remain that way until the space laboratory is eventually de-orbited. Not a bad legacy for a technology initially developed for a simple handshake.