For decades, the United States has attracted students and employees from across the globe aiming to pursue careers in engineering and other STEM disciplines. Foreign-born individuals are a significant part of the U.S. workforce. In recent years, many policymakers and researchers have also sought to better understand and improve the racial and gender diversity of the STEM workforce—but these efforts have largely focused on domestic students.

Byeongdon (Don) Oh, an assistant professor of sociology and the director of the Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging (DEIB) Research Center at SUNY Polytechnic Institute, hopes to gain insight into how immigration status intersects with efforts to foster a more diverse and inclusive STEM workforce. In a recent study, Oh examined data from a national survey of college graduates on race, gender, and immigration status in the U.S. STEM workforce. He found that many immigrants pursue STEM—about one-third of U.S. STEM graduates are foreign-born—but disparities by race and gender are more pronounced among these students than U.S.-born individuals in higher education.

IEEE Spectrum spoke to Oh about the factors driving STEM immigration trends, racial disparities, and the future of STEM immigration. The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Byeongdon Oh on:

Byeongdon Oh: STEM immigration refers to the growing influx of foreign-born individuals seeking STEM degrees or careers in the United States. This increase is certainly influenced by individual choice, because individuals with STEM skills have a good chance at a good career and income in the United States. But it’s not only about individual choice. So many other social forces shape STEM immigration.

Higher education institutions have attracted talented, foreign-born students to support institutional development and generate tuition revenue. Both international students majoring in STEM and high-ranked U.S. universities benefit from each other. There’s also a mutually favorable relationship between foreign-born individuals seeking STEM careers and U.S. employers. Policymakers and employers have expressed a continued need for more STEM workers to support economic growth.

The government also knows that, and the U.S. immigration law have evolved to attract more students and workers with high-level STEM skills. For example, international students cannot work off-campus during their studies. But after graduation, they are allowed to work for one year through the Optional Practical Training program. STEM graduates are eligible for a two-year extension of this period. Many graduates apply for H-1B and permanent residency during that time. STEM immigration is not only an individual choice; it’s increased by many social and structural factors.

What did you find in your research?

Oh: My study finds that about 30 percent of STEM degree holders living in the United States are immigrants. Many discussions have talked about how immigration affects the U.S. economy, and how increasing STEM immigration is affecting the salary rate of native-born workers. This is the first study focusing on how STEM immigration affects the diversity profile of the U.S. STEM workforce.

Oh’s research divides college educated immigrants into three groups: first generation, 1.25 generation, and 1.5 generation.Byeongdon Oh; National Survey of College Graduates

Oh’s research divides college educated immigrants into three groups: first generation, 1.25 generation, and 1.5 generation.Byeongdon Oh; National Survey of College Graduates

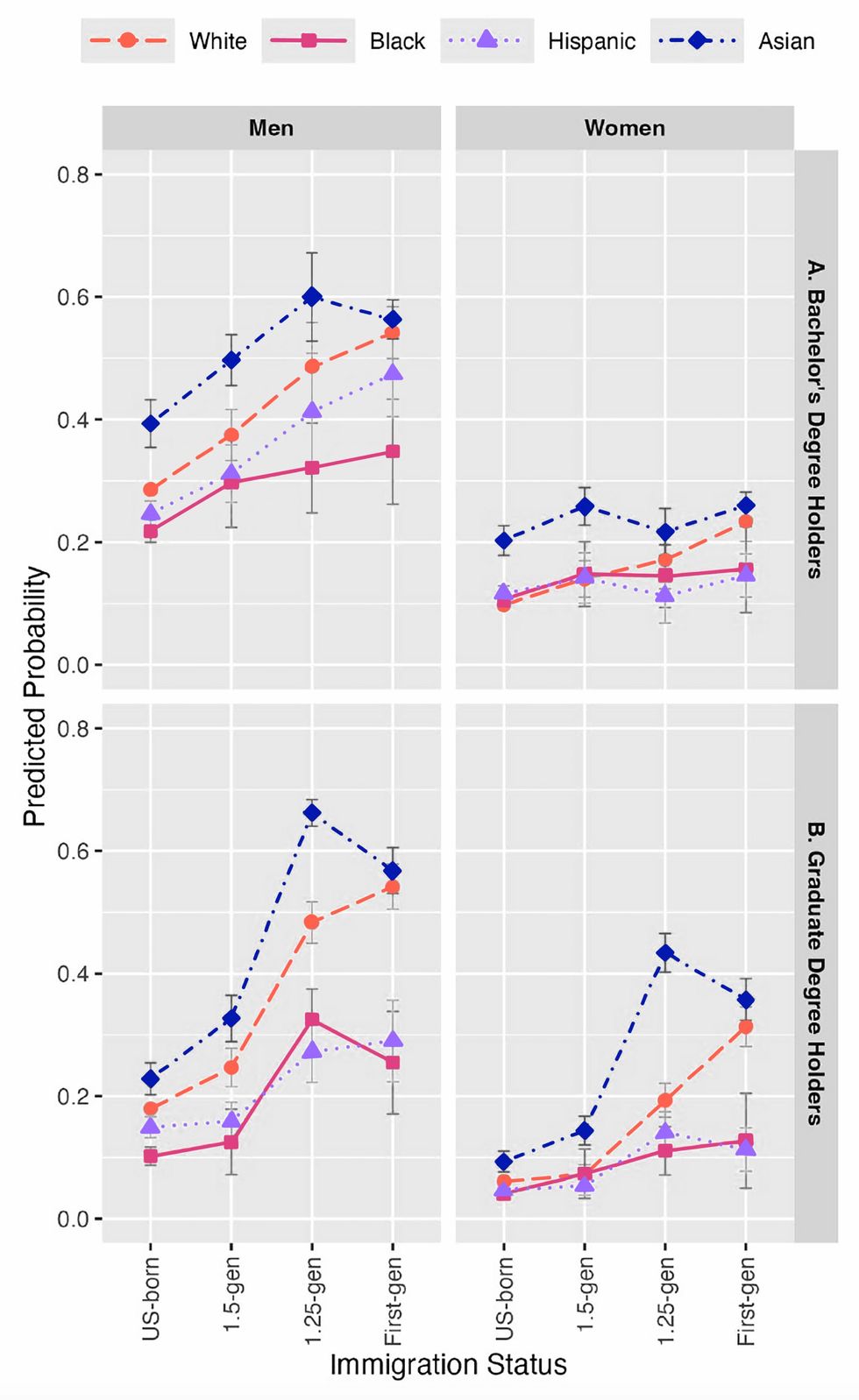

Compared to U.S.-born White graduates, immigrants—regardless of race—are just as likely, if not more so, to hold STEM degrees. However, race and gender disparities are more pronounced among immigrants than among U.S.-born graduates. The gap is already significant among U.S.-born individuals, but it’s even wider among immigrants.

I subdivided college-educated immigrants into first generation, 1.25 generation, and 1.5 generation. The first generation refers to immigrants who complete all of their education outside the United States. The second generation is born in the United States. In my study, 1.5 generation refers to immigrants who obtained a high school diploma in the United States. The 1.25 generation completed a high school diploma abroad, but attended college in the United States. The race and gender gaps in STEM representation are actually widest among the 1.25 generation.

What do you think is causing these disparities?

Oh: This does not come from my data yet, but I suspect there are three major causes. The first originates in the country of origin: Like in the United States, racial and gender disparities can exist within the country of origin. And it’s not only inequality in education or STEM skills. The racial majority and men may also have a better chance to migrate to the United States.

The second factor stems from between-country inequalities. Many White and Asian immigrants come from countries in the Global North, where stronger economies and greater investment in R&D are generally associated with higher quality STEM education.

The third factor relates to the U.S. immigration process. The immigration process is long, and racial minorities and women can be particularly vulnerable to socioeconomic struggles during this long waiting time. Also, employers may hold biases that certain racial groups are better for STEM, or that men are more qualified. That kind of stereotype or discrimination can have an effect. So these could be three major causes, but honestly, we don’t know which one plays the largest role.

Previously, we focused so much on [diversity in] K-12 STEM education and particularly native-born students. But as I said, the 1.25 generation has the widest gap, and there is a substantial volume. So without considering those immigrants, social interventions aimed at diversifying the U.S. STEM workforce will remain limited in their impact.

How can we better support international individuals?

Oh: We need collective social interventions and policy changes. You can think of a short term and long term strategy.

The short-term strategy is to include more immigrants in our policy discussion and debate. Many STEM students and workers are not just coming here as tourists and going back after one or two years. There is a high chance they will stay. If we really want to improve diversity and inclusion in the U.S. STEM workforce, we should include them and learn from their experiences to improve immigration policy.

And long term, we need better data collection. Many government datasets on the immigration process are inaccessible. Immigration researchers really want to have that data, but the government hasn’t granted access to it. Additionally, the federal government requires all higher education institutions to report racial and ethnic profiles annually, using categories similar to those used in the census. But the federal guidelines for higher ed list international students in a separate category. If they are international students, they don’t count race or ethnicity. Many institutions collect that information, but when they report, they place all international students in one category. That’s one example of how we have overlooked race and diversity issues among immigrants.

With recent federal immigration policy changes, we’re seeing early indications that international students may be turning away from seeking higher education in the United States. How does that potential trend relate to your findings?

Oh: The recent policy changes may have short-term negative effects on STEM immigration. When prospective immigrants don’t believe they can successfully settle down in the United States, they may hesitate to start the process. If they see tension between their country and the United States, that can discourage them from pursuing education or employment here. In that way we will lose STEM talent.

In the longer term, I think STEM immigration will continue. There are factors drawing them, like the economy and education. The structural demand for high-skilled STEM students and workers is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

During the first Trump presidency, many STEM immigrants, particularly with graduate degrees, continued to use National Interest Waivers. [That’s an exemption from job offer requirements for advanced degree workers applying for certain visas]. If you have STEM graduate degrees, this provides an expedited pathway to permanent residency. I remember it didn’t decrease. Although immigration is often portrayed in political discourse as a threat to jobs or public safety, having high skilled immigrants helps economic growth. If we lose all STEM immigrants, domestic employers will have a problem.

What’s next for your research?

Oh: I’m pursuing two directions. One is focused on STEM degree holders and the likelihood of entering STEM occupations. Not all STEM degree holders have STEM jobs, and race and gender inequalities may contribute to this education-occupation mismatch. I want to see if these disparities differ by immigration status.

The second direction is qualitative interviews. In my institution, there are many international students and immigrant faculty members. I’m planning to conduct qualitative interviews with them. I’m also a visiting research professor at University of California Berkeley, so I want to compare UC Berkeley and my institution. Ultimately, I hope this line of research can help reframe how we think about diversity—not just in terms of race or gender within the United States, but also across borders and generations.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web