A Wi-Fi system generally includes two or more broadcasters, specifically the primary router unit and one or more satellite units. If you get a purpose-built solution, it’s often available in a 2-pack or 3-pack.

Setting up these units to form a well-performing Wi-Fi system can get tricky. The main question is how to arrange them to deliver the best coverage and performance.

This post will answer that question in detail and offer tips on optimizing your Wi-Fi system, whether via wired backhauling or a fully wireless mesh network. Before continuing, it’s recommended that you read the piece on what a mesh Wi-Fi network is first.

Done? Let’s dive in!

Dong’s note: I first published this post on February 20, 2024, and last updated it with the latest information on August 1, 2025.

Mesh network setup: The general rules of connecting the hardware of a Wi-Fi system

In all Wi-Fi systems, the basic principle is that you use the primary router unit to connect to an Internet source, such as a cable modem, a Fiber-optic ONT, a gateway, or another router, via its WAN port. After that, the rest of the broadcasters work as satellites to extend the network.

In a Wi-Fi system, a satellite unit must be behind the primary router in terms of the network connection. Specifically, it needs to connect to the router directly or indirectly, via a switch or another satellite.

This arrangement is automatically the case in a fully wireless mesh setup. However, in a system with wired backhauling, things can get complicated. You might accidentally put the primary router behind or at the same level as the satellite, such as connecting both to the same switch or existing gateway, which could prevent the system from working as intended.

Wired backhauling: The only way to get the best-performing system

Wired backhauling—where network cables are used to link the broadcasters—is the only way to achieve optimal Wi-Fi performance out of a system. So, getting your home wired is the key to having the best network.

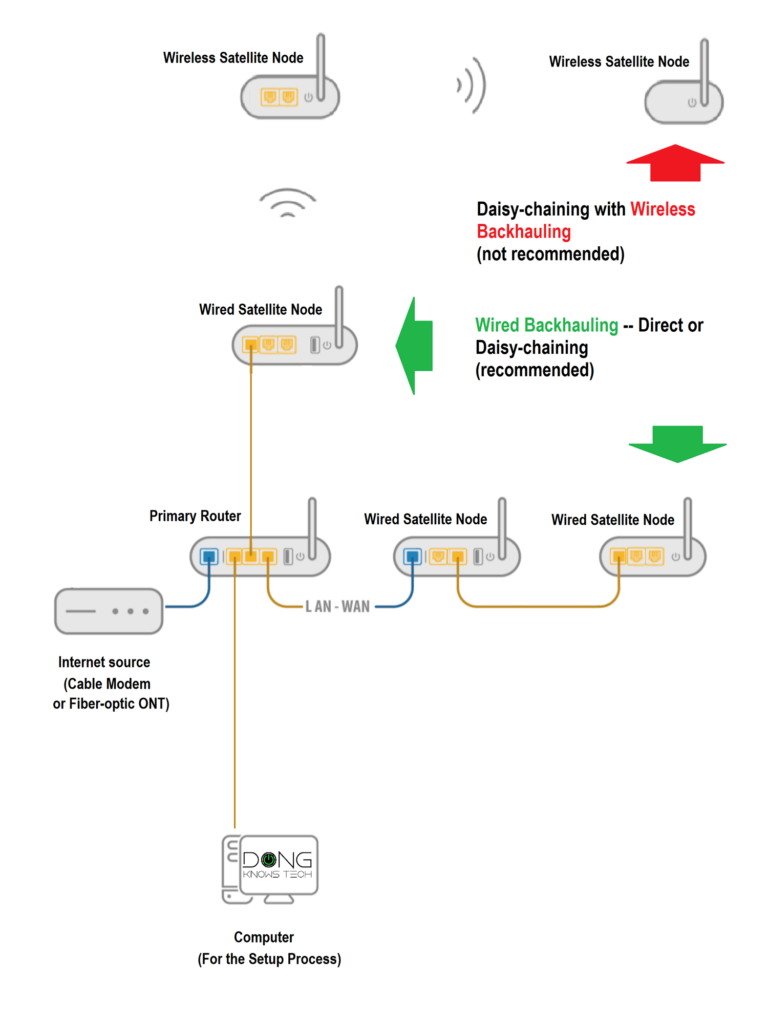

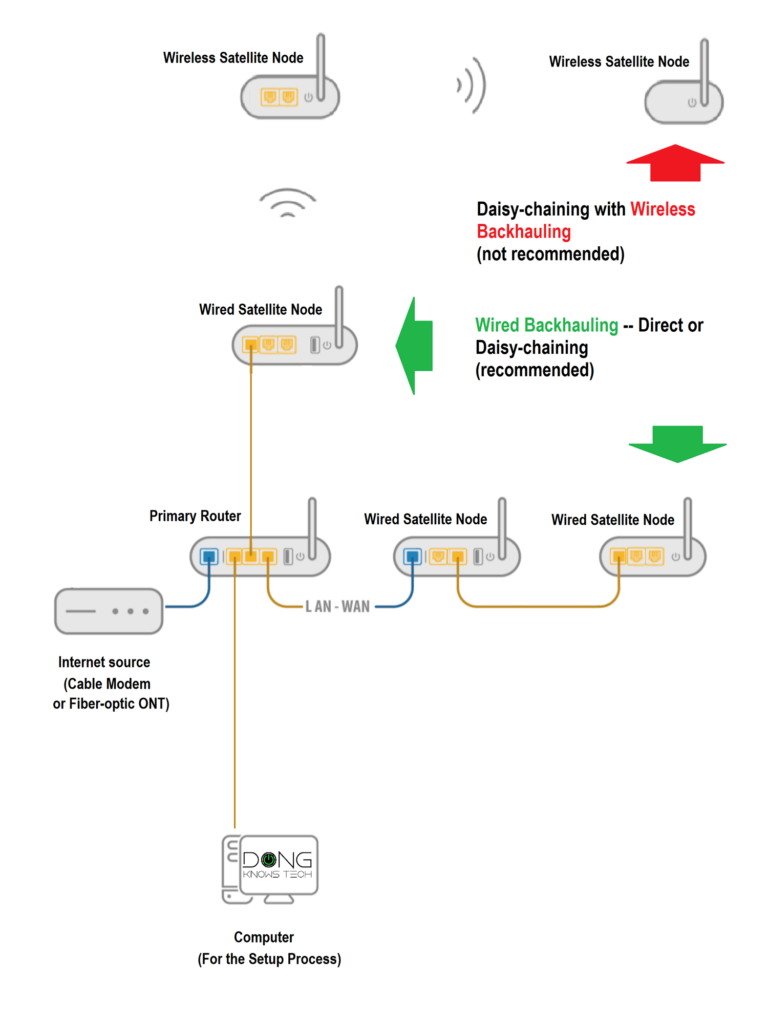

That said, here’s a simple flow to connect a Wi-Fi system’s hardware via network cables, represented by the arrows:

Broadband Internet service line –> Terminal device or gateway (*) –> the primary unit of the system (the router) –> switch(es) / satellite unit(s) –> (switches) –> more satellites.

Again, the key here is that the primary router unit is the only device that connects to the Internet source—or sources in a Dual-WAN situation—and the rest of the devices within the local network need to be behind (or on top of) it. In a Wi-Fi system, all network ports on the satellite unit(s) function as LAN ports.

Below is a diagram of a Wi-Fi system, which includes a primary router and five satellite units connected via both wired and wireless backhauling.

In a fully wired mesh network, you don’t need to worry much about hardware arrangement. Each broadcaster will perform the same regardless of distance (the cable lengths) or placement. Still, it’s a good idea to place them strategically so that they can collectively blanket the desired area without too much overlapping.

In a wired backhaul setup, you can also use unmanaged switches between broadcasters or daisy-chain the mesh hardware—all the more flexible in hardware placement. In this case, note that the performance of the network is always that of the bottleneck device. For example, if you use a Gigabit switch in the network, all devices behind this switch will be limited to Gigabit at best.

However, running network cables can be difficult or even impossible in some situations. So, wireless mesh systems are commonplace. In this case, how you arrange the hardware is crucial.

Wireless backhaul: Proper hardware arrangement is the key to success

Over the air, the wireless connections between the mesh broadcasters can vary greatly depending on each broadcasting unit’s range and the area’s layout. So, in mesh Wi-Fi coverage, there are two things to consider: distance and topology.

1. The distance

That’s the gap between two directly connected broadcasters. The closer you keep them to each other, the stronger the signals are between them, which translates into a faster backhaul link and more bandwidth. The catch is you’ll have less Wi-Fi coverage and probably more interference.

On the other hand, a longer distance means more extensive coverage, but you’ll have a slow Wi-Fi network, especially when the system has to use the 2.4GHz band, which has the most extended range, for backhauling.

It’s tricky to find the sweet spot where the Wi-Fi range balances coverage and speed. Generally, if there are no walls in between, you can place a satellite between 40 ft (12 m) and 50 ft (15 m) from the primary router unit—25 ft to 30 ft is the maximum distance if there are walls.

The easiest way to find out where you should put the satellite is via the signal indicator on your phone or laptop. You want to place it where the signals of the band you intend to use as backhaul, which is often the 5GHz, change from full bars to one or two bars lower.

Ultimately, it’s the speed that matters. If you only need modest network speeds, such as in a home with slow broadband, you can go a bit crazy on the distance to get the most extensive coverage.

2. The topology

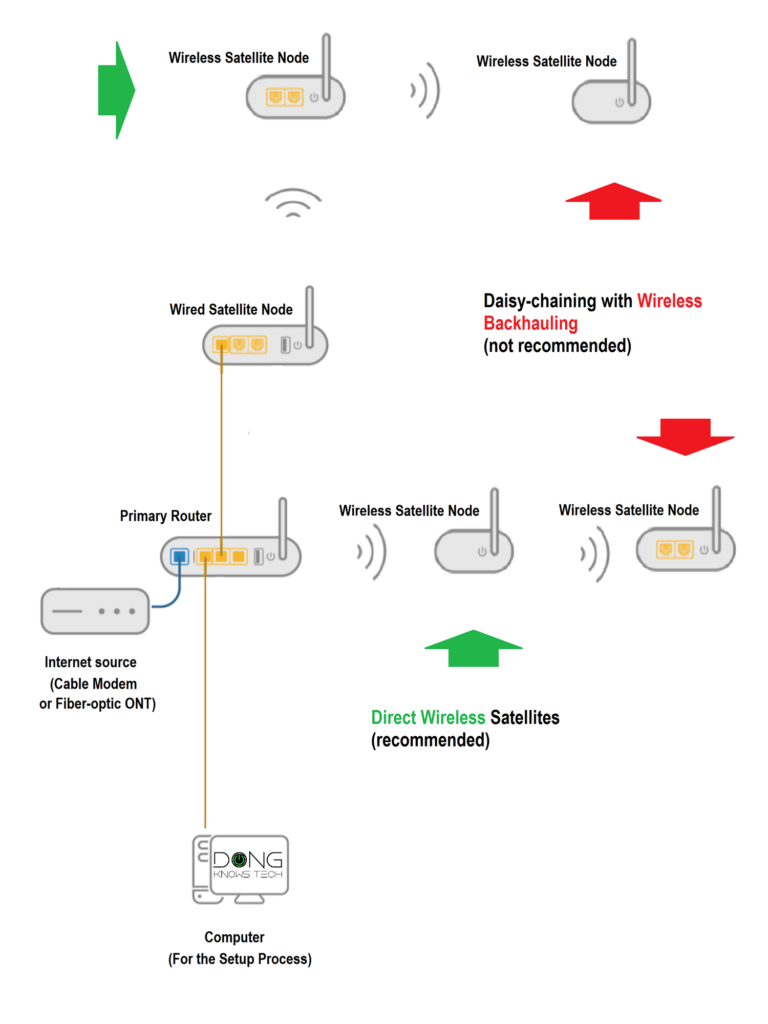

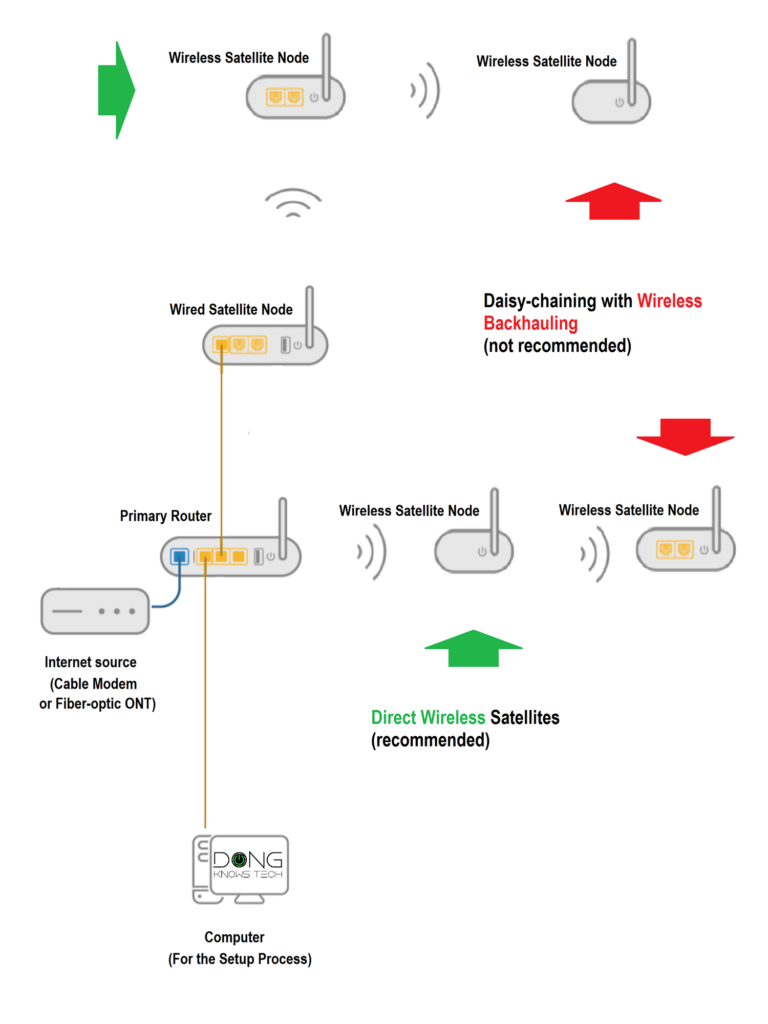

In a wireless setup, signal loss and latency are inevitable. To reduce the adverse effects of the two, you need to use the correct topology, which is the way you arrange the broadcasters. Again, this is relevant only in a system with wireless backhauling and only in a system with three or more hardware broadcasters. Have a 2-pack mesh? You can skip this part—you’d always have the correct topology anyway.

The star topology

This is the recommended topology. In it, you place a wireless satellite directly around the primary router (or a wired satellite node).

This arrangement ensures that each wireless satellite directly connects to a wired broadcaster, namely the system’s primary router or another wired satellite unit. Thus, the Wi-Fi signals hop only once before reaching the end client.

Note: Wi-Fi 7’s MLO as backhaul is generally available between the primary router and its directly-connected wireless satellite.

The daisy-chain topology

The daisy-chain topology refers to a linear arrangement of the hardware units. As a result, the signal has to hop more than once—from a wired broadcaster (such as the primary router) to a wireless satellite, then to another wireless satellite, etc.—before it gets to the device.

In this case, the actual speed will suffer significantly, even when you get full-bar signal strength on the device, and you’ll experience severe lag due to compounded signal loss.

So, in a wireless setup, it’s always a good idea to avoid a daisy-chaining topology.

Mixing wired and wireless backhauling

In many cases, wired backhauling is not possible throughout, and an extra wireless satellite unit is needed at a tricky spot. In this case, apply the wireless backhaul rules above to the wireless portion of your system. After that, keep the following in mind:

- It’s generally better to mix wired and wireless backhauls than pure wireless.

- Only Wi-Fi clients connected to a wireless-backhauled satellite will suffer signal loss. Those connected to a wired broadcaster still enjoy fast—determined by the wired backhaul link, be it Gigaibt or Multi-Gig—and reliable connections.

- It’s best to wire the router to a satellite and then use another wireless satellite (that connects to either).

- It’s OK to wire the satellites together and have either of them connected to the primary router wirelessly. However, in this case, clients connected to any of the satellites will still suffer from signal loss.

Tip

It’s OK to mix wired and wireless backhauling in a Wi-Fi system. In this case, the link between the primary router unit and the first satellite is crucial and should be wired. Using network cables to link the satellites never hurts, but that doesn’t help much if the link between them and the primary unit is wireless.

Generally, hardware with band-splitting, namely Tri-band Wi-Fi 6 and Quad-band Wi-Fi 6E, is best for mixed wired and wireless backhauling. Wi-Fi 7 has so much bandwidth, plus the MLO feature, that the extra band is generally not necessary in a wireless setup. However, considering the standard’s bandwidth, you need wired backhauling to enjoy it truly. Also, to take advantage of MLO, you need to use the same hardware units throughout the system and use them in the star topology as mentioned above.

Extra: Mesh and gaming

This portion of extra content is part of the explainer post on gaming routers.

Mesh Wi-Fi and gaming or real-time communication: The important rules

Generally, get your home wired for the best online experience, including online gaming or whenever you want to ensure the connection is reliable and has the lowest latency.

After that, connect your gaming rig to your network via a cable. No matter how fast, Wi-Fi is always less ideal and will put a few extra milliseconds, or even a lot, on your broadband’s latency.

Reliability and low latency are more critical than fast speeds in gaming or any real-time communication applications. So it’s more a question of wired vs. Wi-Fi than Wi-Fi 5 vs. Wi-Fi 6 vs. Wi-Fi 7.

But we can’t always use wires. That said, the rule in Wi-Fi for gaming is to avoid multiple hops.

Specifically, here is the order of best practices when connecting your gaming device to the network via Wi-Fi:

- Use a single broadcaster—just one Wi-Fi router or access point.

- If you must use multiple broadcasters (like a mesh system), then:

- Use a network cable to link them together (wired backhaul).

- If you must use a wireless mesh, then:

- Connect the game console directly to your home’s first broadcaster—the primary router. Or

- Connect the gaming device to the first mesh satellite node using a network cable. Also, in this case, it’s best to use mesh hardware with an additional 5GHz band unless you have Wi-Fi 7.

- Avoid the daisy-chain mesh setup.

- Avoid using extenders. If you must use one, make sure it’s a tri-band.

Again, the idea is that the Wi-Fi signal should not have to hop wirelessly any additional time before it gets to your device—you’ll get significantly worse latency after each additional hop.

Mesh network setup: The final notes

No matter what type of mesh Wi-Fi network you have, the primary hardware unit should be the only router. If you already have an existing router, such as when you can’t remove the ISP-provided gateway, get a mesh that can work in the access point (AP) mode. In this case, the mesh extends your existing home network without offering any features or particular settings.

You can also turn the existing gateway into a modem by putting it into bridge mode.

Using network cables to link a mesh system’s hardware broadcasters is the best way to build a reliable and high-performance network. If you’re into a robust Wi-Fi system, consider getting your home wired today.