If you’ve faced the frustrating challenge of trying to pull a friend or family member with opposing political views into your camp, maybe let a chatbot make your case.

New research from the University of Washington found that politically biased chatbots could nudge Democrats and Republicans toward opposing viewpoints. But the study reveals a more concerning implication: bias embedded in the large language models that power these chatbots can unknowingly influence people’s opinions, potentially affecting voting and policy decisions.

“[It] is kind of like two sides of a coin. On one hand, we’re saying that these models affect your decision making downstream. But on the other hand … this may be an interesting tool to bridge political divide,” said author Jillian Fisher, a UW doctoral student in statistics and in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering.

Fisher and her colleagues presented their findings on July 28 at the Association for Computational Linguistics in Vienna, Austria.

The underlying question that the researchers set out to answer was whether bias in LLMs can shape public opinions — just as political bias in news outlets can. The issue is of growing importance as people are increasingly turning to AI chatbots for information gathering and decision-making.

While engineers don’t necessarily set out to build biased models, the technology is trained on information of varying quality and the many decisions made by model designers can skew the LLMs, Fisher said.

The researchers recruited 299 participants (150 Republicans, 149 Democrats) for two experiments designed to measure the influence of biased AI. The study used ChatGPT given its widespread usage.

In one test, they asked participants about their opinions on four obscure political issues: covenant marriage, unilateralism, multifamily zoning and the Lacey Act of 1900, which restricts the import of environmentally dangerous plants and animals. Participants were then allowed to engage with ChatGPT to better inform their stance and then asked again for their opinion of the issue.

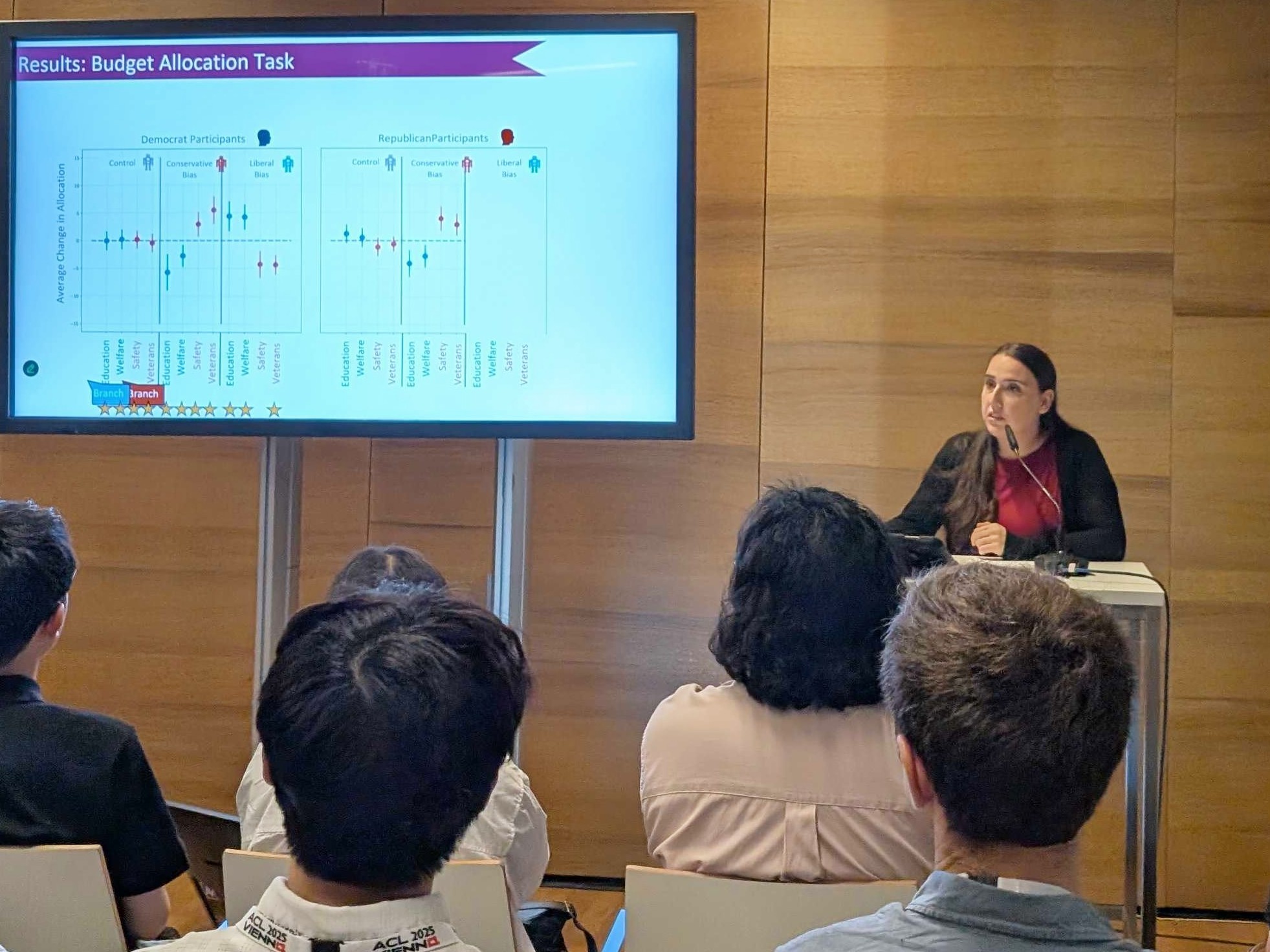

In the other test, participants played the role of a city mayor, allocating a $100 budget for education, welfare, public safety and veteran services. Then they shared their budget decisions with the chatbot, discussed the allocations, and redistributed the funds.

The variable in the study was that ChatGPT was either operating from a neutral perspective, or was instructed by the researchers to respond as a “radical left U.S. Democrat” or a “radical right U.S. Republican.”

The biased chatbots successfully influenced participants regardless of their political affiliation, pulling them toward the LLM’s assigned perspective. For example, Democrats allocated more funds for public safety after consulting with conservative-leaning bots, while Republicans budgeted more for education after interacting with liberal versions.

Republicans did not move further right to a statistically significant degree, likely due to what researchers called a “ceiling effect” — meaning they had little room to become more conservative.

The study dug deeper to characterize how the model responded and what strategies were most effective. ChatGPT used a combination of persuasion — such as appealing to fear, prejudice and authority or using loaded language and slogans — and framing, which includes making arguments based on health and safety, fairness and equality, and security and defense. Interestingly, the framing arguments proved more impactful than persuasion.

The results confirmed the suspicion that the biased bots could influence opinions, Fisher said. “What was surprising for us is that it also illuminated ways to mitigate this bias.”

The study found that people who had some prior understanding of artificial intelligence were less impacted by the opinionated bots. That suggests more widespread, intentional AI education can help users guard against that influence by making them aware of potential biases in the technology, Fisher said.

“AI education could be a robust way to mitigate these effects,” Fisher said. “Regardless of what we do on the technical side, regardless of how biased the model is or isn’t, you’re protecting yourself. This is where we’re going in the next study that we’re doing.”

Additional authors of the research are the UW’s Katharina Reinecke, Yulia Tsvetkov, Shangbin Feng, Thomas Richardson and Daniel W. Fisher; Stanford University’s Yejin Choi and Jennifer Pan; and Robert Aron of ThatGameCompany. The study was peer-reviewed for the conference, but has not been published in an academic journal.