When configuring a home router, you’ll run into many Wi-Fi settings with cryptic names.

If you have no idea what they mean and find it hard to know the correct value to enter, you’re not alone. I myself have a hard time remembering all those acronyms or keeping track of the various ways different networking vendors inconsistently call the same things.

This post will explain the common ones among these pesky Wi-Fi settings in friendly language. When you’re done, you’ll be able to configure your home network more confidently.

It’s worth noting, though, that many of these settings are like switches and buttons under the hood of a car. And as such, you generally should leave them alone and use the default (auto) values. Still, an inquiring mind will find this post a satisfying read.

Dong’s note: I first published this piece on September 26, 2022, and updated it on January 17, 2026, with up-to-date information.

Wi-Fi Settings: Untangling the common yet confusing names

The first thing to note when handing Wi-Fi is that access points (standalone or integrated into a router) follow the same principles as the Wi-Fi standard(s) they support.

Still, depending on the brand, Wi-Fi hardware often doesn’t offer the same level of customization—some have more than others. So, it’s normal if your beloved Wi-Fi router doesn’t have everything I’m about to mention, or if it has something else I will miss.

Secondly, generally only standard hardware with a web user interface offers access to all the possible settings of a Wi-Fi access point (or Wi-Fi router). App-operated hardware, such as a purpose-built home mesh system, often comes with a limited set of Wi-Fi settings.

Finally, regardless of brand or complexity, all Wi-Fi hardware shares a set of common settings listed below.

Let’s dive in!

Common Wi-Fi settings

Again, these settings are available on all Wi-Fi access points and routers, but the details, depth, and even the naming vary.

Radio (a.k.a Wi-Fi band)

Radio is the hardware that broadcasts the Wi-Fi signals. Generally, each Wi-Fi band—2.4GHz, 5GHz, or 6GHz—is a piece of radio hardware. So a dual-band router has two bands, a tri-band router has three, and so on.

In some hardware units, you can enable or disable a band, permanently or on a schedule. When all bands are turned off on a Wi-Fi router, it becomes a non-Wi-Fi router—or just a “router”.

There are a few scenarios when you want to turn off a Wi-Fi band: to avoid interference (especially in a double-NAT situation), to reduce energy consumption, or just because you can.

In most cases, you don’t need to worry about this setting.

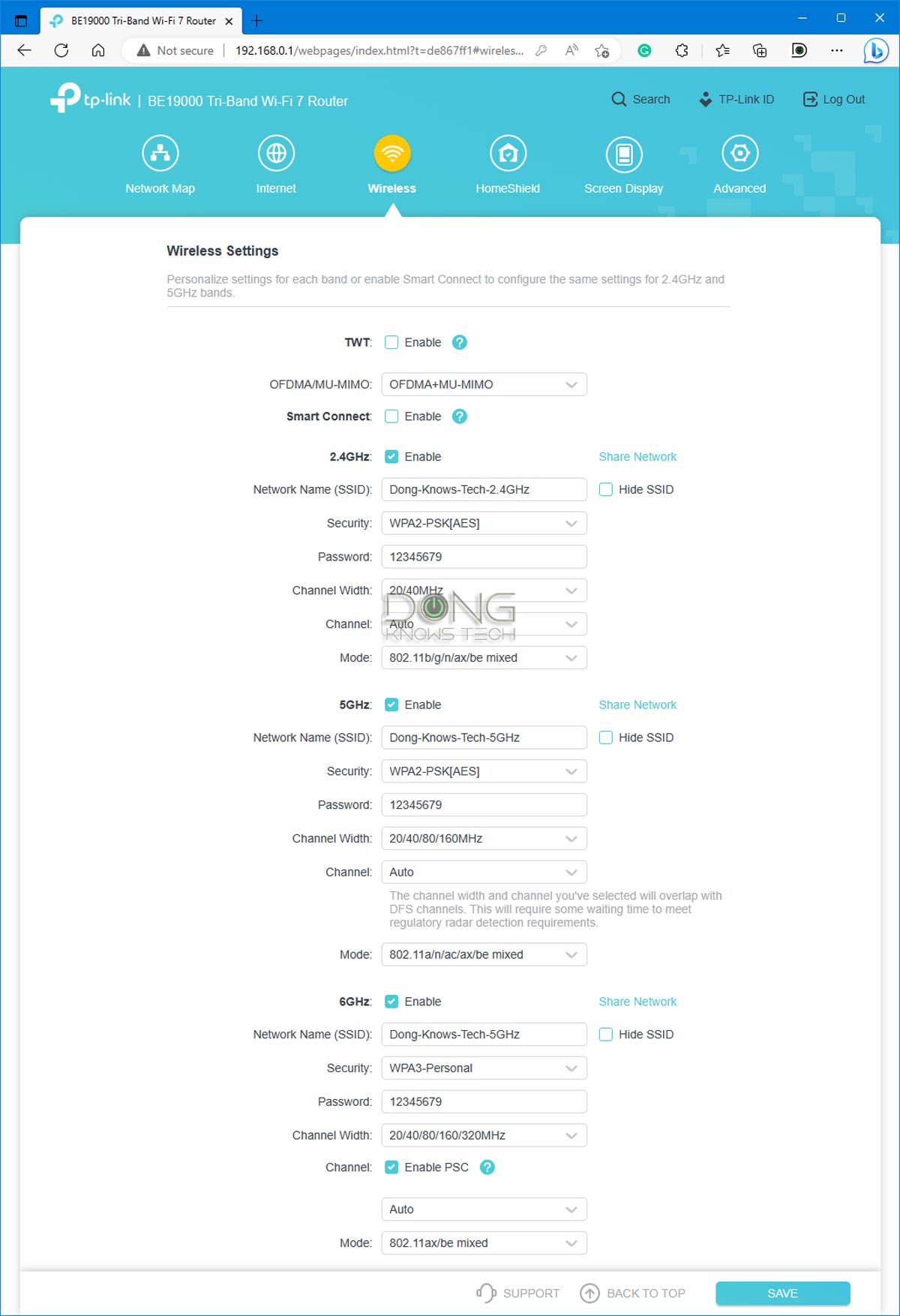

Wi-Fi standard (a.ka. Wi-Fi mode or Wireless Mode)

As the name suggests, this setting dictates to clients which Wi-Fi standard(s) a band supports, such as 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7), 802.11ax (Wi-Fi 6), or 802.11ac (Wi-Fi 5).

The default value (Auto), recommended for compatibility, means the band will handle all clients across all Wi-Fi standards. This compatibility mode may reduce real-world performance of the latest hardware, but forcing a band to work with a specific standard often means legacy (old) clients can’t connect.

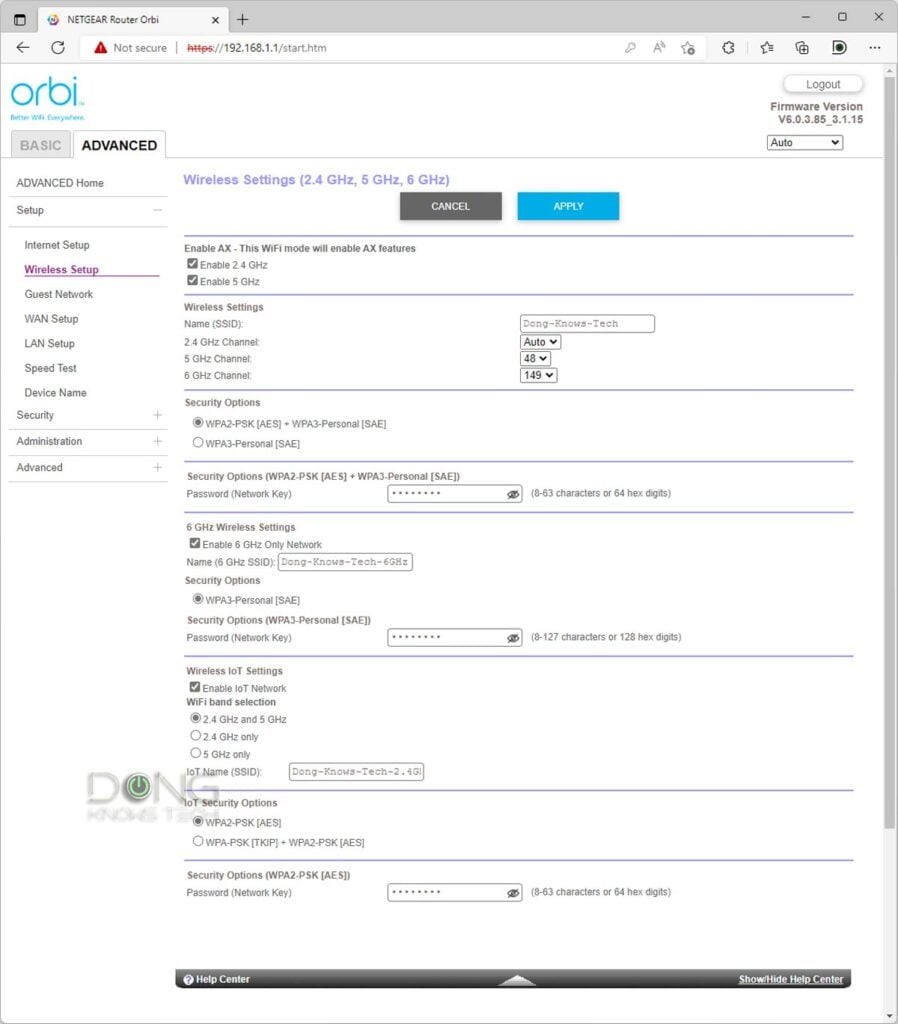

Wi-Fi name (a.k.a SSID)

Wi-Fi name—often called network name, wireless name, etc.—is the friendly moniker for the Service Set Identifier (SSID) that a Wi-Fi band uses to broadcast its signals.

An SSID appears on a device’s Wi-Fi scanner when you attempt connect it to a new network for the first time. As a name, you can make it anything you want, but it’s best to use plain text with no spaces or special characters and keep it short and sweet.

By default, an SSID is shown publicly, but you can choose to hide it (for security or privacy reasons). If so, you’ll need to manually enter the SSID into the device each time you connect a new client to the network.

An SSID can be open, allowing any device to connect, or protected with a password to restrict access. More information on this topic is in the Wi-Fi Security section below.

Virtual Wi-Fi networks (SSIDs): Guest, IoT, MLO, etc.

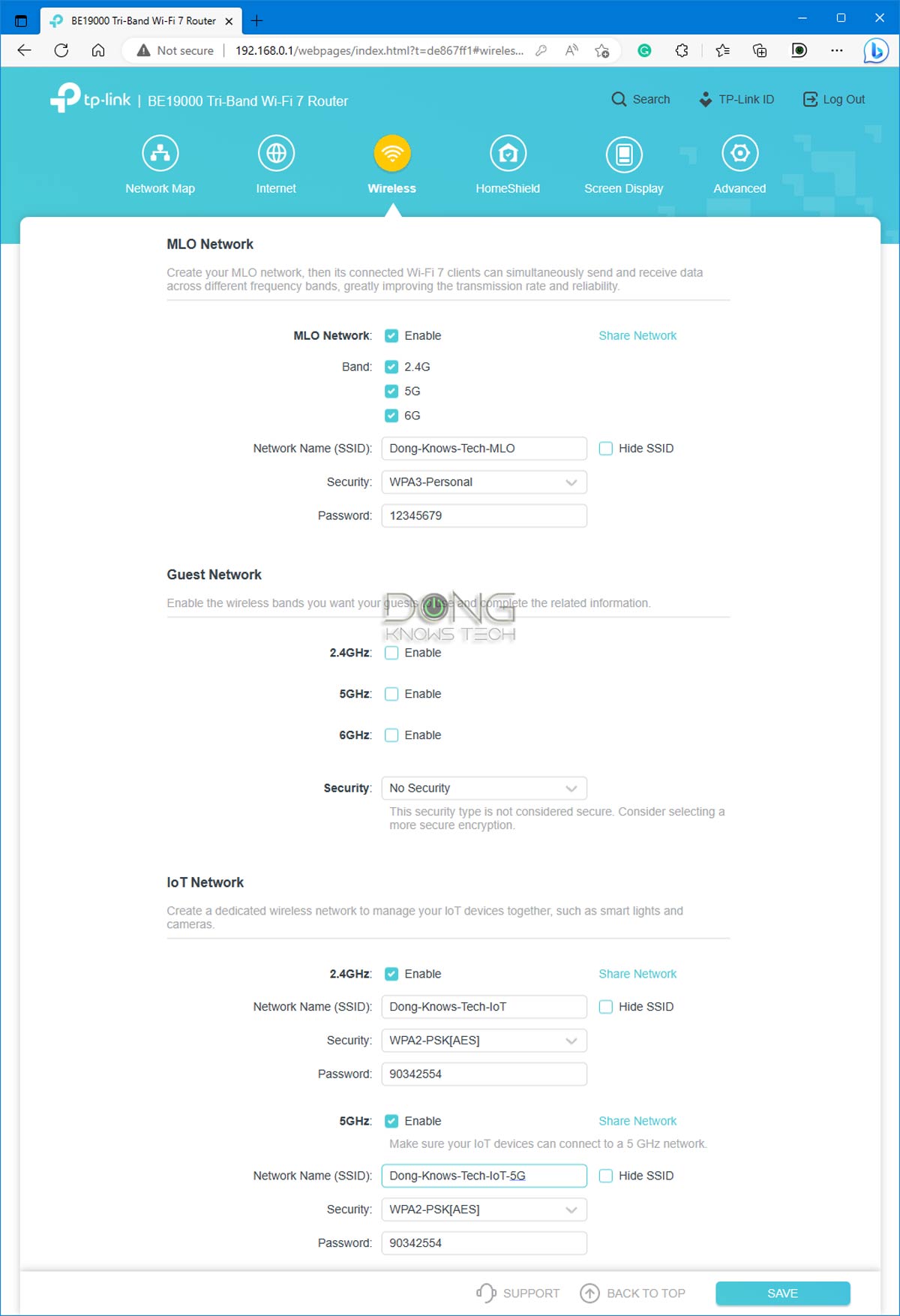

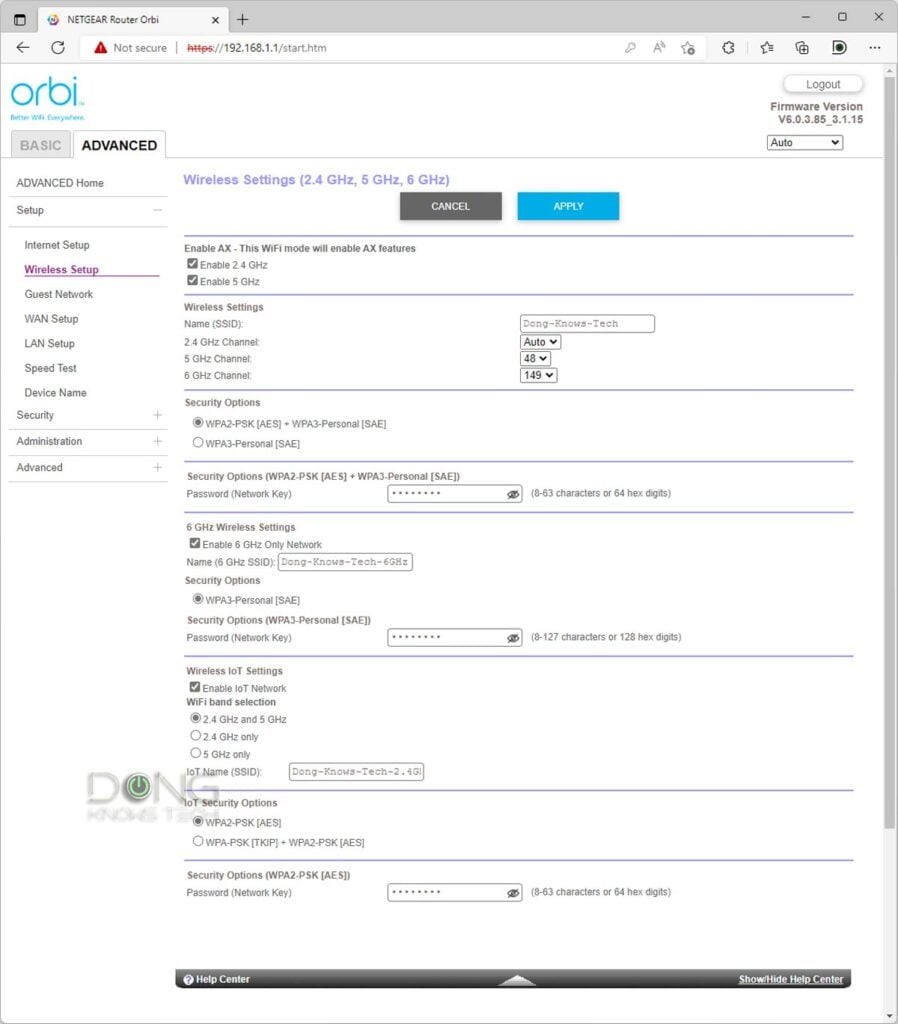

Generally, each Wi-Fi band has an SSID, referred to as the “primary” or “main” SSID. However, in most cases, you can create multiple virtual SSIDs to segment the network for different purposes, such as supporting legacy devices that don’t meet the latest security or performance requirements.

The following are the popular examples of virtual SSIDs:

- Guest Wi-Fi network: Often automatically formed by adding “-Guest” as the suffix to the main SSID’s name. This is an isolated network designed to allow Internet access but not local resources, such as shared folders or printers, as a local security measure.

- IoT network: Often automatically formed by adding “-IoT” as the suffix. This is a virtual, non-isolated Wi-Fi network supposedly designed to handle Internet of Thing Wi-Fi smart devices that require lower security requirements—more on security below—which would otherwise compromise the performance of the primary SSID.

- MLO network: This SSID is often automatically generated by adding “-MLO” as a suffix when available. Available starting with Wi-Fi 7, MLO (short for Multi-Link Operation) combines multiple bands into a single network to deliver higher bandwidth and reliability.

Generally, you can rename these virtual SSIDs to your liking—the suffixes are not required. Some even allow additional settings such as bandwidth limits or scheduled availability.

Virtual SSIDs, unless further customized, inherit the same characteristics as the primary SSID, including security, channel, and bandwidth—more on these below.

Wireless scheduler (a.k.a SSID schedule)

This setting allows users to disable an SSID on a schedule when it’s not needed or wanted, such as when you want the household to stay offline.

Smart Connect: Lumping all bands into a single SSID

Smart Connect is a technique applicable to access points with multiple Wi-Fi bands (Dual-band, Tri-band, or Quad-band), enabling a single SSID to be used across all of them.

For Smart Connect to work, the hardware uses Smart Connect Rule, a.k.a Band Steering, to determine which band a client will connect to.

Band Steering (a.k.a Smart Connect Rule)

Band Steering—applicable when Smart Connect is used or when you use the same network name (SSID) and password for multiple bands—automatically steers clients between the bands based on set parameters. Generally, the purpose is to optimize the usage of each band’s bandwidth.

The idea is that the clients will connect at the fastest speed possible by connecting to the best band in real-time.

In reality, Band Steering doesn’t work well among home routers, where clients might end up connecting to the slowest band (2.4GHz) simply because it has the highest signal strength, thanks to its extensive range.

Generally, Smart Connect is a convenient way to stay connected if you don’t mind not connecting to the fastest band (5GHz or 6GHz) at all times. Additionally, in many cases (not all), Smart Connect doesn’t allow for customizing each band individually. If so, all bands will use compatibility-favored settings and not the settings optimized for best performance.

“Dumb” Connect: Using separate SSIDs across the bands

If you want more control over which band or bands your device uses, turn Smart Connect off and assign each band to a separate SSID.

In this case, if you assign two or more SSIDs the same name and password, you’ll achieve a similar effect to Smart Connect. Generally, a client would pick whichever band (sharing the same SSID) is faster and has a signal strength above a certain dBm threshold to connect. The success rate will vary depending on the clients.

Using a unique SSID for a particular band is the only way to ensure that you can connect a specific deviceusing that band at all times. It also offers the most in-depth settings, including the fastest-performance options.

Wi-Fi Channel

A Wi-Fi band is a large radio frequency segment divided into smaller portions called “channels”. By default, each Wi-Fi channel—often represented by a number in a drop-down menu—is 20MHz wide. This is the minimum width supported by all Wi-Fi hardware.

That brings us to a few sub-settings:

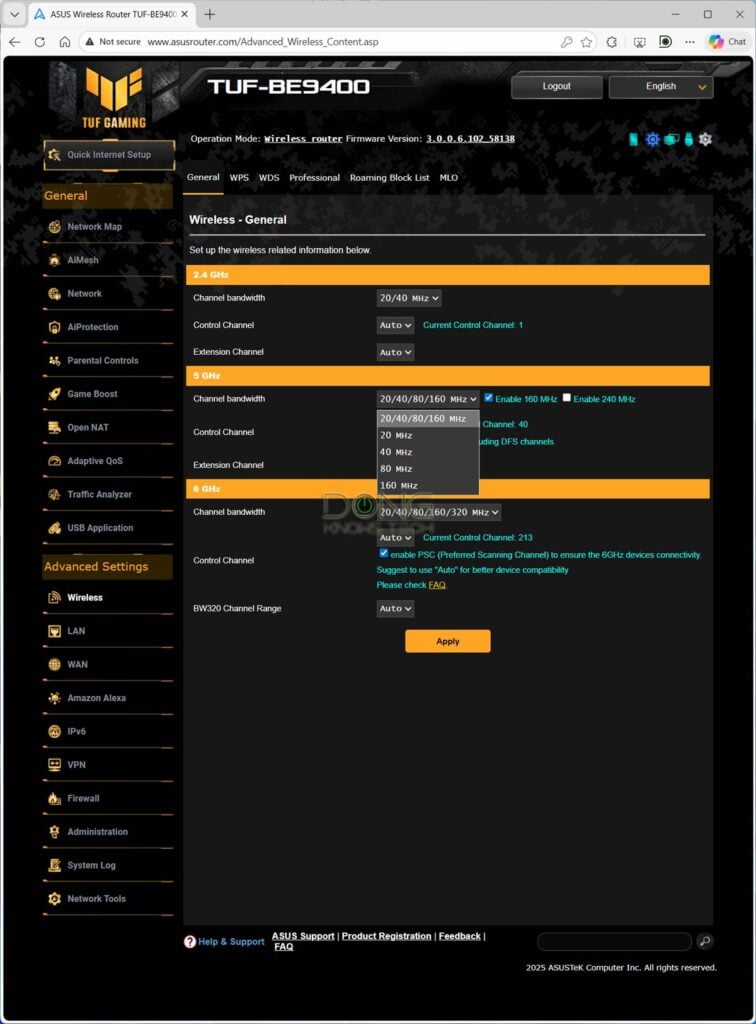

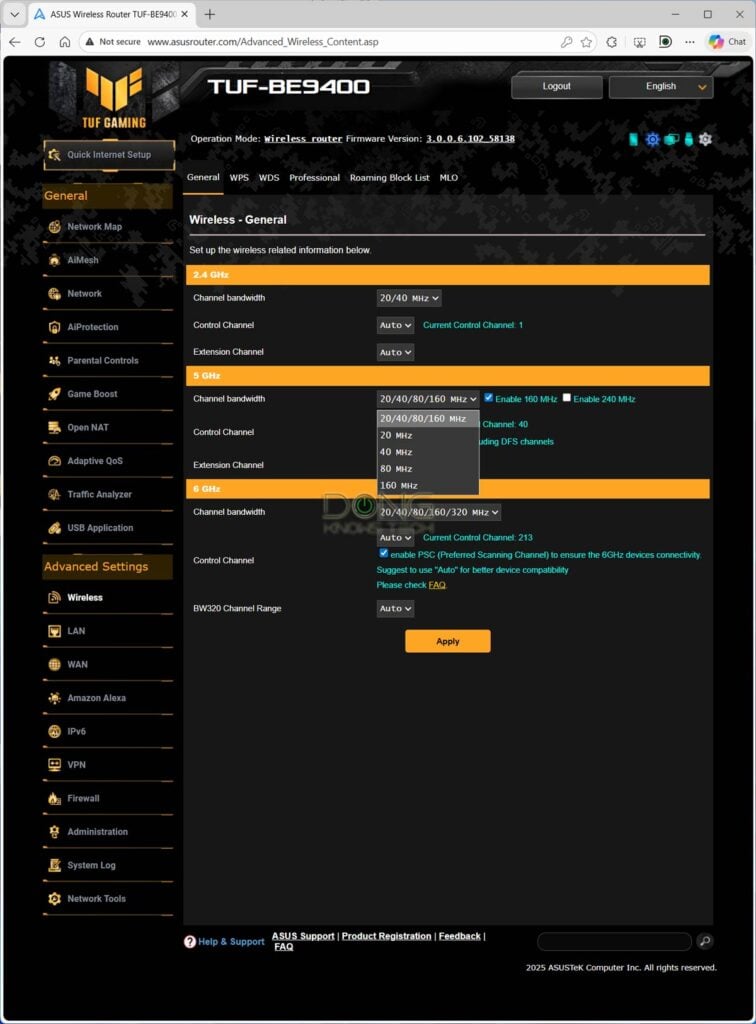

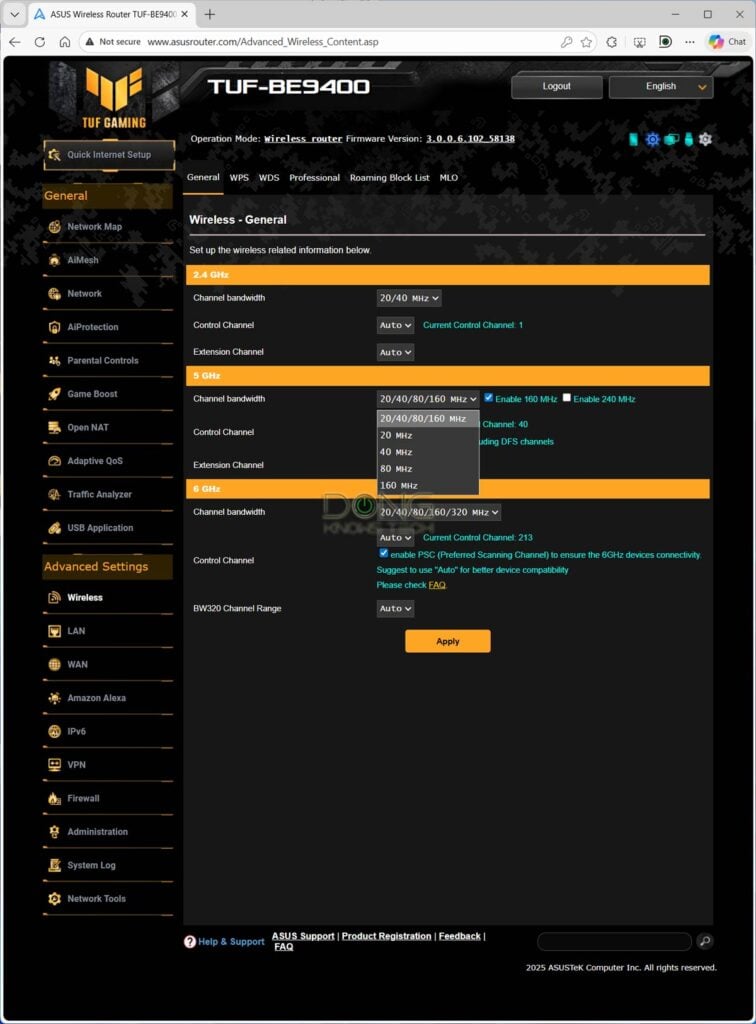

Channel Width (a.k.a Bandwidth)

The name says it all. This setting determines the channel width used, measured in MHz. The wider the channel, the larger portion of the Wi-Fi band it occupies, the more bandwidth it has, and the faster it can be.

Depending on the Wi-Fi standards and bands, a Wi-Fi channel is 20MHz (default), 40MHz, 80MHz, 160MHz, 240MHz, or 320MHz wide. The wider a channel is, the less compatible it becomes—legacy clients can only use channels of a certain maximum width. When possible, select a width that suits your needs, or use the hardware’s Auto setting to apply the appropriate value in real-time.

A wider channel consists of two or more contiguous 20MHz channels, which brings us to the Control Channel and Extension Channel settings.

Control Channel

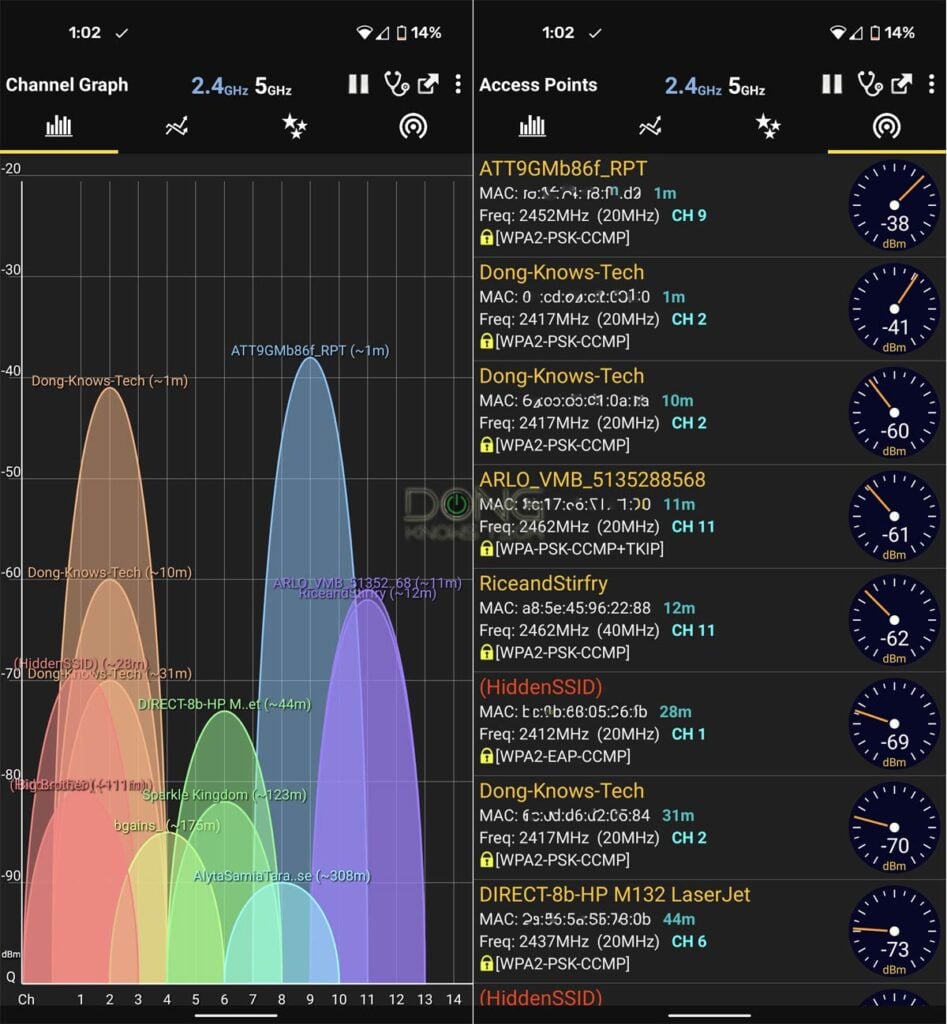

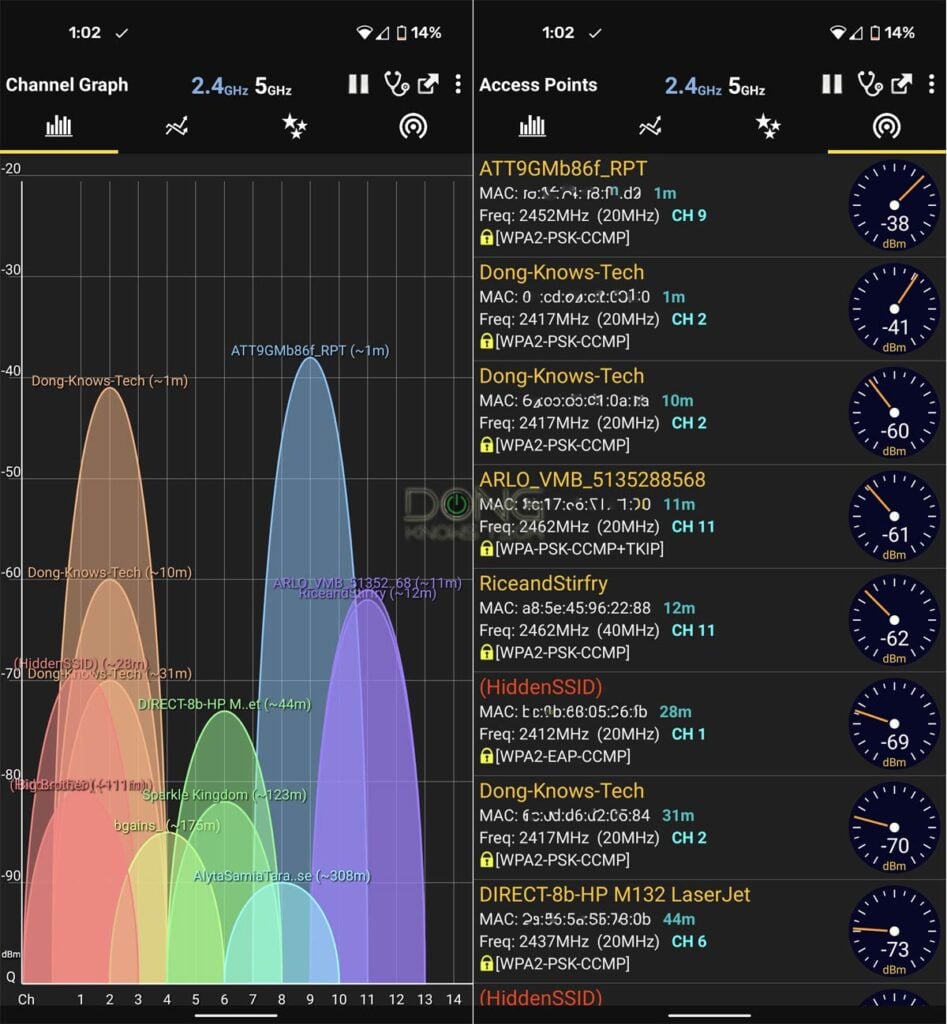

That’s the specific 20MHz channel you pick from the list. If you leave the value at Auto, the hardware will pick one automatically for you.

Extension Channel

This setting dictates the direction—up, down, or both—the hardware will use to extend the Control Channel by combining it with adjacent channels to fulfill the Channel Width setting above.

When available—this setting is not common in all hardware—depending on where the Control Channel is on the spectrum, you can choose the value of the Extension Channel to be Above or Below, or you can leave it at Auto.

Generally, you want to pick the Control and Extension channels that form a channel whose width is not at least overlapped with other access points within the vicinity—it’s a way to make your network more reliable. When in doubt, use the Auto settings to allow the hardware to pick the optimal one in real-time.

Important: Forcing an access point to operate on a specific channel or channel bandwidth might cause incompatibility with clients—for example, no client can connect to the UNII-4 portion of the 5GHz frequency band. For example, a 20MHz client can’t connect to a 40MHz or wider channel, a 40MHz client can’t connect to an 80MHz or wider channel, and so on.

By default, all Wi-Fi access points (or routers) automatically use compatible settings, or warn you when you manually pick settings that are not applicable to real-world conditions. Using this default compatibility setting, often shown as “Auto”, is the safest option and should be applied first when there are connection issues.

DFS channel (a.k.a DFS channel selection or DFS)

Short for Dynamic Frequency Selection, DFS refers to channels shared with non-Wi-Fi applications, such as RADAR, in the 5GHz frequency band.

When the access point is elected to use a DFS channel, it takes a back seat, meaning it will automatically switch to another channel if another application needs it.

The use of DFS increases the channel width and, therefore, Wi-Fi bandwidth, but may also cause intermittent, brief disconnections.

Wi-Fi bands vs. channels vs. stream

Wi-Fi uses three frequency bands: 2.4GHz, 5GHz, and 6GHz. The width of each band is measured in MHz—the wider the band, the more MHz it has. Depending on local regulations, only a section or sections of a band are allowed for Wi-Fi use.

In real-world usage, the Wi-Fi-allowed section of each band is divided into multiple smaller portions, called channels, of different fixed widths. Depending on the Wi-Fi standards and bands, a channel can be 20MHz, 40MHz, 80MHz, 160MHz, 240MHz, or 320MHz wide. The wider a channel is, the more bandwidth it has. The number of channels in each Wi-Fi band varies depending on the channel width and the width of the Wi-Fi-allowed section of the band.

Data moves in one channel of a particular band at a time, using streams, often dual-stream (2×2), three-stream (3×3), or quad-stream (4×4). The more streams, the more data can travel simultaneously. Thanks to the ultra-high bandwidth per stream, Wi-Fi 6 and later tend to have only 2×2 clients.

Here’s a crude analogy:

If a Wi-Fi band is a freeway, channels are lanes, and streams are vehicles (bicycles vs. cars vs. buses). On the same road, you can combine multiple adjacent standard lanes (20MHz) into a larger one (40 MHz, 80 MHz, or higher) to accommodate oversized vehicles (a higher number of streams) that carry more goods (data) per trip (connection).

A Wi-Fi connection generally occurs on a single channel (lane) of a single band (road) at a time. The actual data transmission is always that of the lowest denominator—a bicycle can carry just one person at a relatively slow speed, even when used on a super-wide lane of an open freeway.

Wi-Fi Security

Since Wi-Fi signals are democratically broadcast in the air, by default, all devices can connect to them, which can be a security issue. To restrict the connections, all Wi-Fi access points and routers have a security measure that includes the following settings:

Authentication Method (a.k.a Security Standard, Security Option, or Security Level)

This is the type of security the hardware uses among these:

- Open (or Open System, or Enhanced Open): No security. This setting is available in all Wi-Fi standards and hardware, allowing any clients to connect to the access point. It’s applicable when you don’t need to restrict access for any client, or when you have different types of restrictions, such as SSID isolation (like a Guest network).

- WEP: Short for Wired Equivalent Privacy, a dated, obsolete security method used in legacy hardware (Wi-Fi 4 and older).

- WPA: Short for Wi-Fi Protected Access, which replaces WEP as a better security method. Starting with Wi-Fi 5, WPA is required. With WPA, we have the following sub-settings:

- WPA Encryption: When WPA is used, there are two encryption options: Temporal Key Integrity Protocol (TKIP) and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). The latter is more secure and the only option in WPA2 and WPA3.

- WPA-Personal vs. WPA-Enterprise: WPA (all versions) supports both Personal (default) and Enterprise modes. The former applies to most situations and requires a Pre-Shared Key; the latter is for Enterprise applications and requires a RADIUS server. More on these below.

- Group Key Rotation Interval (also known as Key Rotation) is a WPA security feature that automatically refreshes (renews) the encryption key to prevent “guessing” attacks. The default value is 3600 seconds (1 hour), which is generally the ideal interval. Shorter values might seem more secure, but are unnecessary and can cause the hardware to overwork.

- WPA2: Commercially available in 2006, WPA2 is an enhanced version of WPA that utilizes the AES encryption method and introduces the Counter Cipher Mode with Block Chaining Message Authentication Code Protocol (CCMP) as a replacement for TKIP. All Wi-Fi 5 and new devices support WPA2.

- WPA3: The latest security method introduced in 2018 to do away with WPA2. It was first introduced with Wi-Fi 6. Some Wi-Fi 5 hardware also supports this method as an option, while others don’t. Starting with Wi-Fi 6E, WPA3 is mandatory.

- OWE (short for Opportunistic Wireless Encryption): Introduced in 2018 as part of the Wi-Fi Alliance’s Wi-Fi Certified Enhanced Open program, OWE is the alternative to the Open type mentioned above. Applicable to public Wi-Fi hotspots, OWE provides a safer approach to a non-secure network by automatically isolating connected devices from one another.

When selecting a security option, remember that the higher the WPA version, the more secure the Wi-Fi network becomes, but the less compatible it is with older clients.

For example, WPA3 is only universally supported in Wi-Fi 6E and newer clients. If you use only this standard, it’s a sure thing that many existing clients will not be able to connect to your Wi-Fi network. So, better security isn’t necessarily always “better” in real-world usage.

In most cases, you can and should choose a mix of these standards. In this case:

- Use WPA or WPA/WPA2 for legacy clients.

- Use WPA2/WPA3 or WPA3 for modern clients.

When in doubt and if possible, pick WPA. It’s secure enough. Many Wi-Fi access points (or routers) offer multiple virtual SSIDs, each with its own security standard options. In this case, you can create multiple Wi-Fi networks for different client types.

WPA Pre-Shared Key (a.k.a Wi-Fi Password)

WPA Pre-Shared Key—also known as a network key, network password, or simply password—is a secret string of text and numbers that grants a client access to the Wi-Fi network. In short, it’s the password you’d need to type in before you can connect a client to a secure Wi-Fi network.

RADIUS

Short for Remote Authentication Dial-In User Service, RADIUS is a server that provides enterprise-grade authentication, replacing traditional passwords. When RADIUS is used, a user authenticates themselves using a username and password to connect to a Wi-Fi network, similar to logging in to an email account or a business domain server.

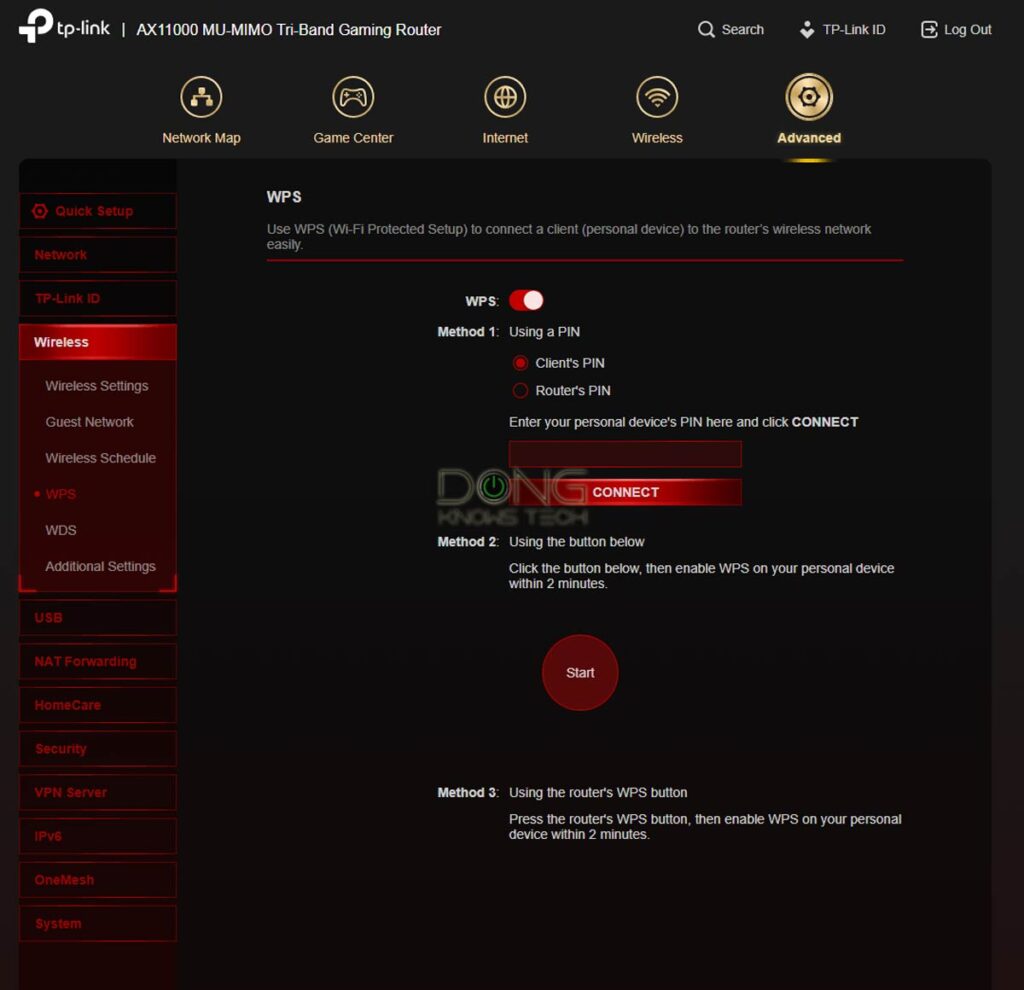

WPS

Short for Wi-Fi Protected Setup, WPS is a quick method for adding a client to a Wi-Fi network—either via a hardware button or a button on the router’s interface. This method is also often used to link a Wi-Fi access point to an existing one to form a mesh system.

The idea is to press the WPS button on the router (if available) and, within 120 seconds, press it again on the client. The two will automatically connect, saving you the hassle of entering the Wi-Fi password.

WPS makes life easier—especially when you need to add an Internet of Things (IoTs) device, such as a printer, to the network—but it has been proven to be a security loophole in specific situations. The 120-second window mentioned above could be used by a third party to connect an unauthorized device.

Thus, for practical and security reasons, many modern Wi-Fi hardware no longer has a hardware WPS button, and the software WPS function is often disabled by default. In this case, you can choose to use this function or not, and when you don’t, it doesn’t pose a security risk.

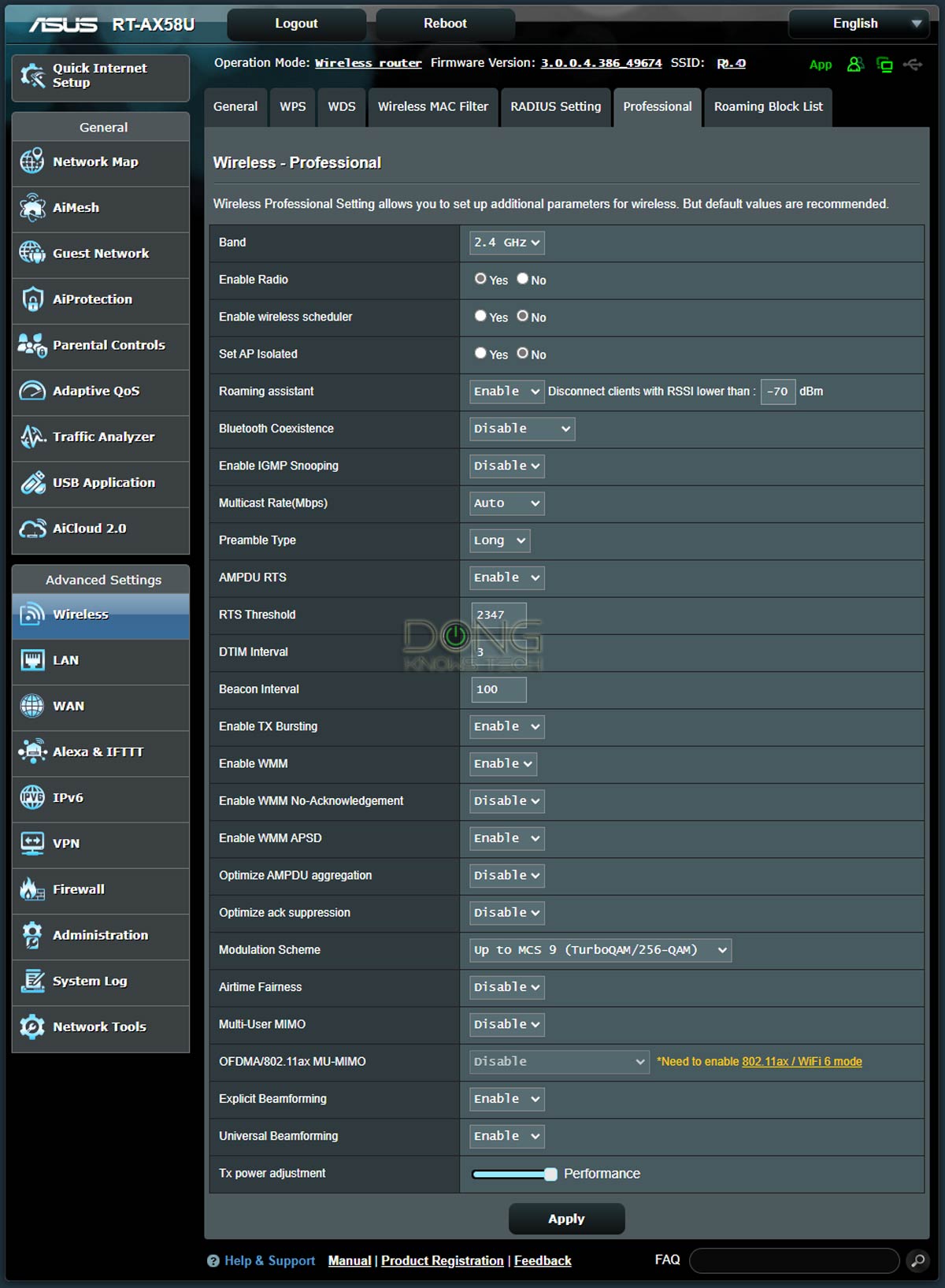

Less common Wi-Fi settings

Many access points don’t offer users access to these settings, and in those that do, the default values are the “safest”—you might want to leave them alone.

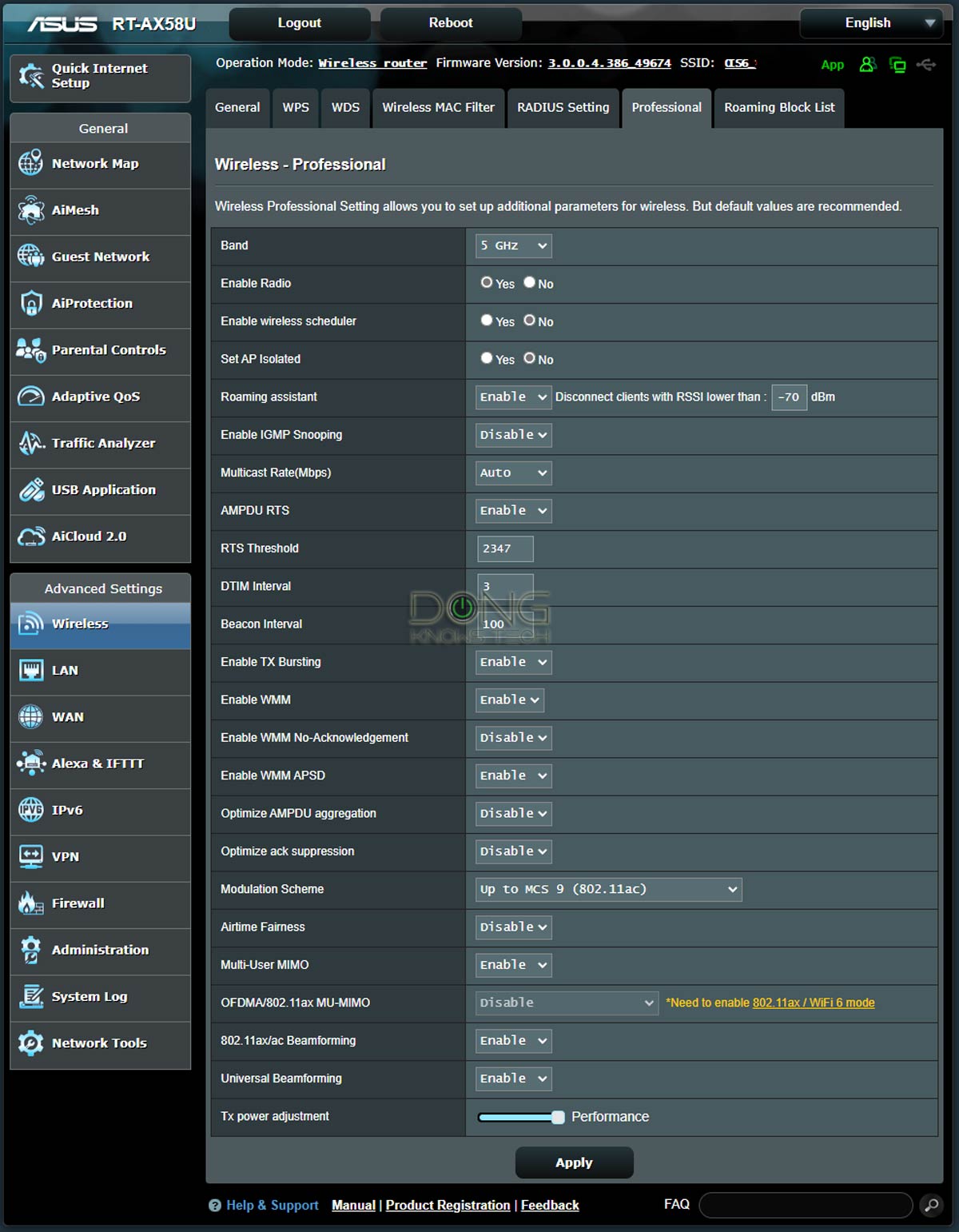

Airtime Fairness

When enabled, this setting enhances the performance of fast Wi-Fi clients at the expense of slower ones. Depending on the situation, it might also cause an access point to overwork.

I detailed Airtime Fairness in this post. Generally, I recommend leaving this setting off (default), starting with Wi-Fi 6.

SSID Isolation (a.k.a AP or network Isolation/Isolated)

Isolation prevents connected devices from communicating locally. All they can access is the Internet. By default, isolation is disabled, except for Guest networks, where it is enabled.

Roaming Assistant (a.k.a Roaming or Handoff or Seamless Handoff)

This setting is similar to the Band Steering above, but only at the access point. It’s applicable only to a network that includes multiple Wi-Fi units, such as a mesh Wi-Fi system.

Handoff is referred to differently by vendors, but the principle is generally the same—it helps a Wi-Fi device select the best (often the closest) access point (or mesh unit) to connect to as you move around a large area.

Here’s a detailed post on roaming assistants for those using an ASUS AiMesh system. Generally, the default (best) roaming setting is -70 dBm.

Broadcasting power (a.k.a TX Power, Transmit Power)

Generally, a Wi-Fi band broadcasts at the maximum power allowed by the region—in the US, that’s 30 dBm or 1 watt. This setting allows you to adjust the power to any level below the current setting. Lower levels lessen an access point’s coverage.

USB Mode (a.k.a Downgrade USB…)

Applicable to a router with a built-in USB 3.0 port. This setting toggles between USB 3.0 mode (default) and USB 2.0. The latter helps improve the performance of the 2.4GHz band.

If you want to use a router’s USB port to host a storage device, USB 3.0 mode is recommended (at the expense of the 2.4GHz band’s performance).

Less common Wi-Fi settings

The table below includes less common Wi-Fi settings. In most cases, you should leave them alone.

| Setting Name |

Default value |

What it does |

|---|---|---|

| Wi-Fi Agile Multiband | Enabled | Better performance for this band, but it must be supported by clients, and can cause issues for those that don’t. |

| Target Wake Time | Enabled | Target wake time (TWT) is a new feature of Wi-Fi 6 and later that allows a Wi-Fi router or access point to manage activity in the Wi-Fi network to minimize medium contention between connected clients and reduce the required amount of time a client in the power-save mode needs to be awake. |

| (Enable) IGMP Snooping | Off | A method that the router uses to identify multicast groups, which are groups of computers or devices that all receive the same network traffic. It enables switches to forward packets to the correct devices in their network. |

| Multicast Rate | Auto | The rate at which a router puts messages in groups to send out as multicast to avoid collisions. This setting boosts performance at the expense of latency. It’s best to leave it at Auto. |

| Preamble Type | Long | An error-checking utility or function that helps with data transmission. Long Preamble Type can improve the transmission if the wireless signals are weak. |

| AMPDU (a.k.a AMPDU-RTS)| Optimize AMPDU Aggregation |

on|off | Aggregated MAC Protocol Data Unit (AMPDU) deals with congestion problems by aggregating multiple MPDU blocks together. When turned on, this setting improves performance in crowded airspace. However, you should have it off if you want to run critical applications such as video conferencing or voice-over IP. The Optimize AMPDU Aggregation further optimizes AMPDU. |

| RTS Threshold | 2346 (bytes) |

The Request to Send (RTS) Threshold is the required packet size (in bytes) that the access point has to check if a handshake is required with the receiving client. If the value is 2346 or higher, RTS is effectively disabled. |

| DTIM Interval | 3 | This setting helps devices discover broadcasting access points to switch between them in a mesh system. High values (in milliseconds) can improve performance by saving resources, but they make it harder for clients to switch from one AP to another. |

| Beacon Interval | 100 (milliseconds) |

The time between beacon frames that are transmitted by a Wi-Fi access point. The AP radio will transmit one beacon for each SSID it has enabled at each beacon interval. |

| Enable TX Bursting | on | A legacy setting that improves performance for 802.11b and 802.11g clients and has no effect on newer clients. |

| WMM APSD | enabled | The Wi-Fi Multimedia (WMM) Automatic Power Save Delivery (WMM APSD) helps mobile clients save battery while connected to the Wi-Fi network by allowing them to enter standby or sleep mode |

| Protected Management Frames (PMF) | 6GHz: Required 5GHz: Capable 2.4GHz: Disabled |

Protected Management Frames (PMF) is a standard defined by Wi-Fi Alliance to enhance Wi-Fi connection safety. It provides unicast and multicast management actions and frames a secure method with WPA2/WPA3, which can improve packet privacy protection. |

| Fragmentation Threshold | 2346 (bytes) |

The maximum length of the frame, in bytes, beyond which packets must be fragmented into two or more frames. The default value is 2346, which effectively disables fragmentation. Low fragmentation thresholds may result in poor network performance. |

| Modulation Scheme | Up to the highest possible | The level of Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) is being used for the band. The higher the number, the more bandwidth. |

| Turbo QAM (2.4 GHz only) |

on | Better performance for this band, but it must be supported by the client and can cause issues for those that don’t. |

| Beamforming | on | Steers the Wi-Fi signals between Wi-Fi hardware for a better connection. Both ends must support this setting for it to take effect. There are different flavors of Beamforming—Explicit Beamforming (2.4GHz), 802.11ac Beamforming (5GHz), and Universal Beamforming—but they all vary from brand to brand. None is a universally standard feature. |

The takeaway

There you go. The information above will be helpful if you want to tinker with your hardware to optimize your home Wi-Fi network.

The rule is to back up the device’s settings before making any changes, and when you’re at it, remember that the best can sometimes indeed be the enemy of the good. Not so sure? Leave the default values alone.